Well, it just gets worse and worse, doesn’t it.

For the second season in a row it feels like a fixture against Sheffield Wednesday, after a poor run of results that followed a pretty lucky/unsustainable unbeaten run feels likely to decide a manager’s fate.

Saturday’s 2-2 draw to Cardiff, with a very late set-piece equaliser saving Stoke from a feeling of the sky falling in, wasn’t enough for fans. The boos rang out in the bet365 Stadium, and honestly, who can blame them?

No other relegated side, since Stoke first came into the Championship in 2018, has gone without a play-off campaign after dropping out of the Premier League.

It seems like the fans’ view has shifted significantly, with talk of unfair Profit & Sustainability Rules, ‘Not His Squad’, and ‘He Just Needs Time’ fading out in favour of a deeper frustration with the past 8 years of Stoke City. With no top half finishes to speak of, and another relegation battle possibly looming, there appears to be very little credit left in the bank for the club’s hierarchy.

Let’s take a look at what the data shows about Stoke’s most recent fall in performances, which unfortunately appears to have been off a rather large cliff.

Has It Been All That Bad?

In a word: yes. In more words: yes, it has been that bad.

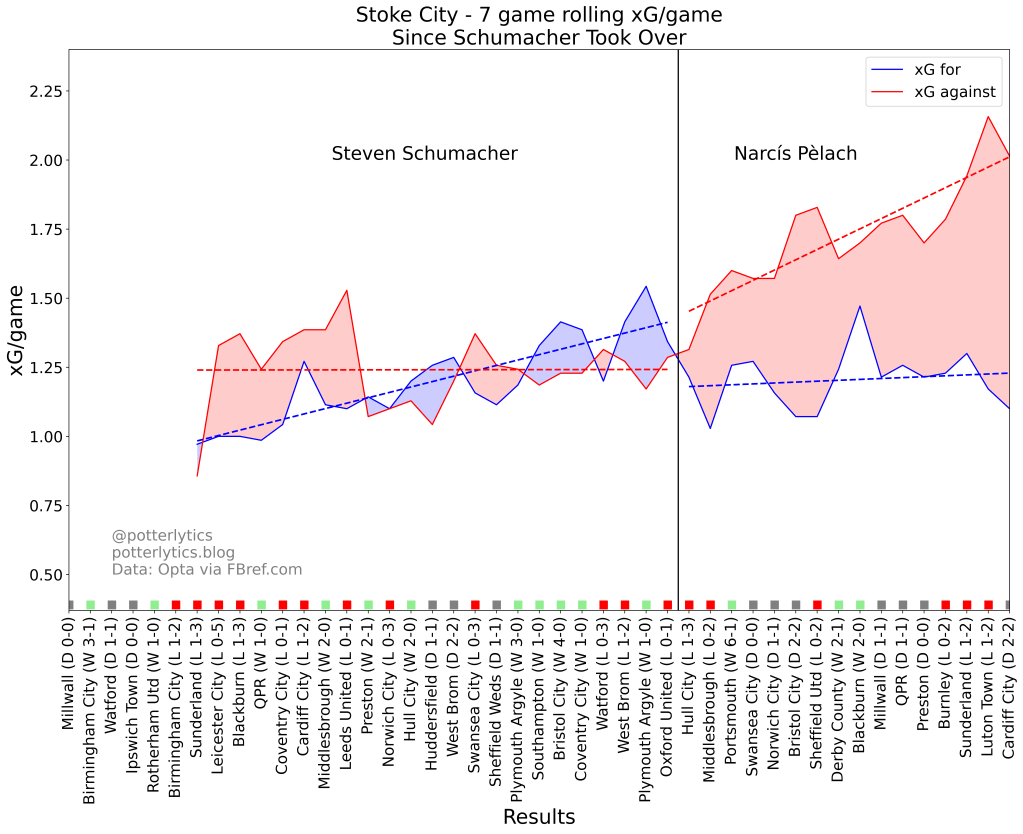

Since Narcis Pelach took over, Stoke’s underlying numbers have plummeted to one of the worst in the division, creating more than their opposition in just 2 of his 17 games in charge.

With 16 points from 16 league games, and some big slices bad luck in some poor refereeing decisions (particularly in draws at home to Millwall and away at QPR), it was hoped that Pèlach’s recent run of form – 4 points from 7 games with no win – is somewhat of an anomaly, having only lost 1 game from 10 prior to the Burnley match.

But as a big data nerd – as I sit here and look at and play with all my silly machines as much as I like – the performances tell a different story.

Whilst Stoke’s attacking numbers under Pèlach have remained relatively stable (although certainly not impressive), their defensive numbers have been shot directly downwards into the Mariana Trench by a howitzer.

It’s interesting that even in the run of 1 loss in 10, Stoke were still putting up poor underlying numbers, and after this perfect example of the role of data as a measure of ‘sustainability’, I think this is something I’ll point to forever as a reason to use it to predict future performance, rather than relying on results.

Looking at the table, Stoke have only conceded 28 in 21 (22 in 16 under Pèlach), with 4 of those being own goals (more on that later). This disconnect is why I’m not too keen to call Pèlach and the team currently ‘unlucky’ for those poor decisions.

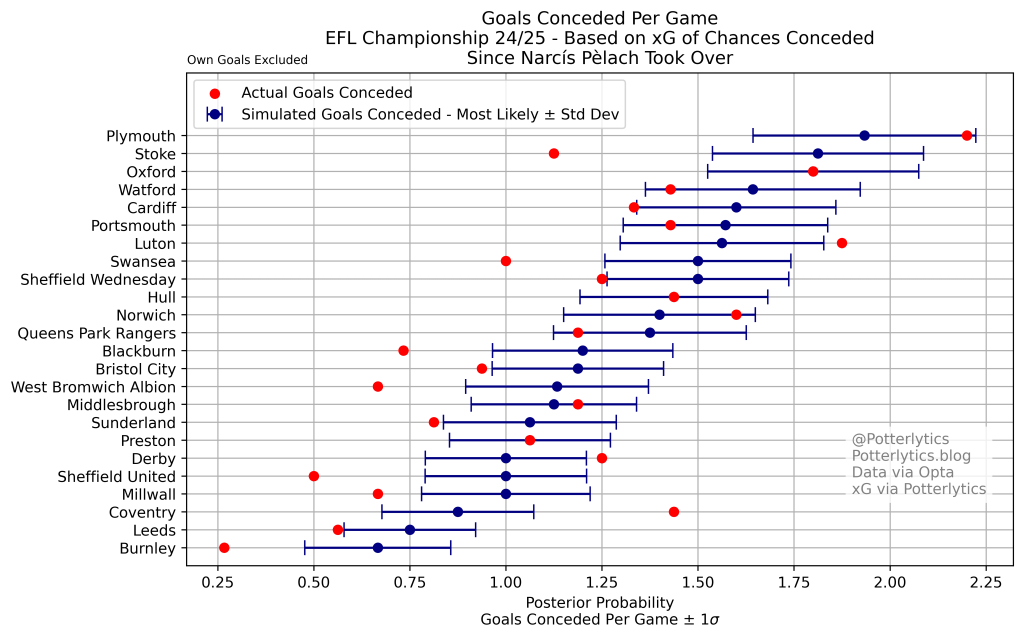

To quantify that defensive ‘luck’, using the chances they’ve conceded in games since Pèlach took over, we can calculate the probability that Stoke concede the number of goals they have conceded in that time.

Simulating their shots 100,000 times (own goals excluded), we find that the most likely number of goals for Stoke to concede in their 16 league games under Pèlach is 29, compared to the 18 they’ve actually conceded.

In fact, in 99,585 of the 100,000 simulations, Stoke conceded more goals than they have in real life.

For those with a willingness to debase football with technical jargon, they’re almost 3 standard deviations away from the mean prediction.

Looking at the rest of the league for comparison, only Plymouth conceded more on average in the simulations than Stoke, with the Potters about level with Oxford (who incidentally just sacked Des Buckingham) in terms of predicted goals conceded per game.

In fact, no other team is ‘luckier’ – in that no other team has a higher probability of conceding more goals than they have – than Stoke, with Sheffield United close behind.

Not Just A Brick Wall, A 10m Thick Nuclear Bunker

A huge part of that is down to Viktor Johansson, with the Swedish number 1 conceding an incredible 11 (eleven) goals fewer than expected for the shots he’s faced.

In fact, no other Championship goalkeeper has excelled by such a margin in shot-stopping since FBref started measuring Post-Shot Expected Goals.

PSxG is similar to xG, but instead of predicting how likely a chance is to be scored before the shot, it takes the trajectory of the shot after it’s taken, and predicts how likely it is to be scored based on historical data. So, for example, Peter Crouch’s volley against Manchester City had a low xG (far out, difficult chance), but a high PSxG (struck powerfully into the top corner).

As you can likely judge from the plot above, being high up means good shot-stopping, and Johansson is so far above the rest as to almost be in my previous blog post.

As Narcís Pèlach was keen to point out, the defensive shape – a very deep, very compact and narrow block – was in place not necessarily to prevent opposition shots, but to prevent them getting clear cut chances. As much as that has likely helped Johansson exceed expectations by giving him a smaller area of the goal to cover, it’s certainly a push to say it’s been ‘working’.

Defending The Space

The first of the two major tactical issues is one I’ve written about in depth before on here, so I won’t dwell on it too much, but the ultra-conservative low block, that Stoke are desperate to get back into and rely on, has started to bring the results I feared it might back in early November.

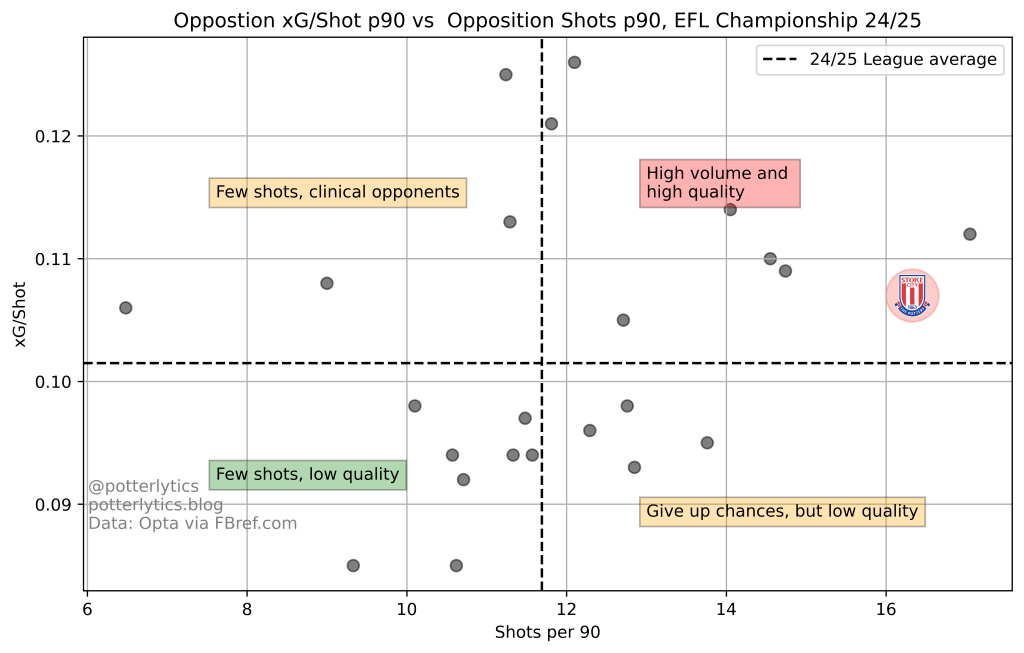

Stoke have now conceded more shots than any other team in the division, and more xG than all but one side in Plymouth Argyle. They’re not close to the defences above them either, sitting almost 5xG conceded worse than Oxford United.

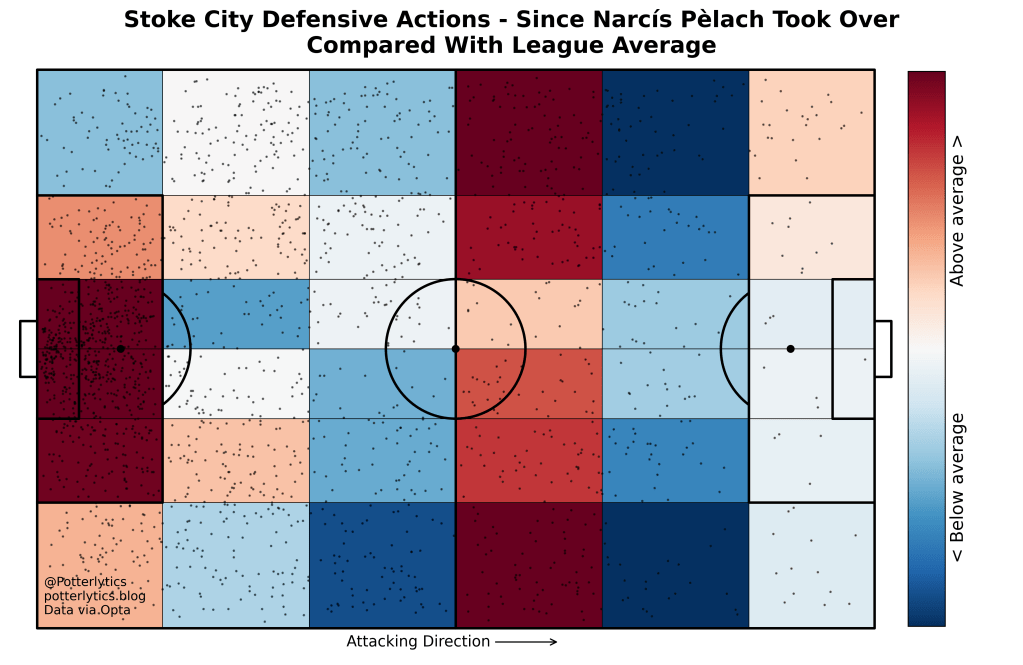

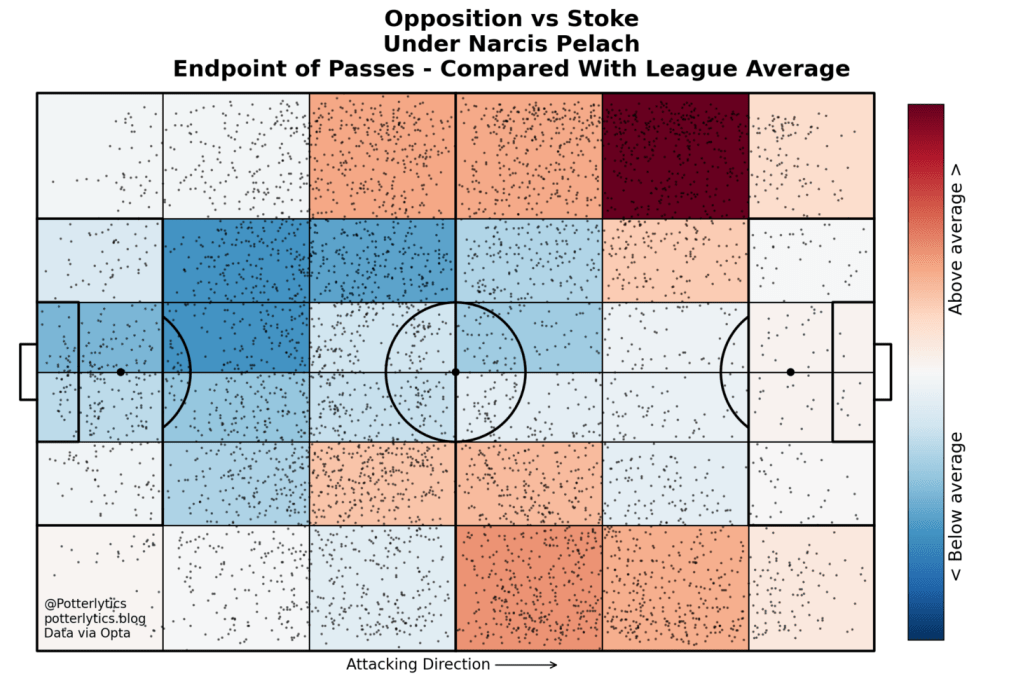

Reposting the plot above, we see that Stoke look to pretty much defend 2 areas and 2 areas only.

Firstly, they sit in a mid-block, and force the ball wide in the opposition’s half – indicated by the big red strip just inside the opposition half, with the darker red areas in wide positions.

If that gets bypassed, they then sit incredibly deep in their own penalty area and essentially concede the space in front of their own box – indicated by the red penalty area and the blue/white areas outside their own box – hoping to get enough bodies between the ball and the goal to prevent a big opportunity.

The idea is clear, defend the most dangerous areas of the pitch, and don’t allow the opposition to have uncontested possession close to your goal.

But the ideas have been muddled, and as Narcís Pèlach himself put it:

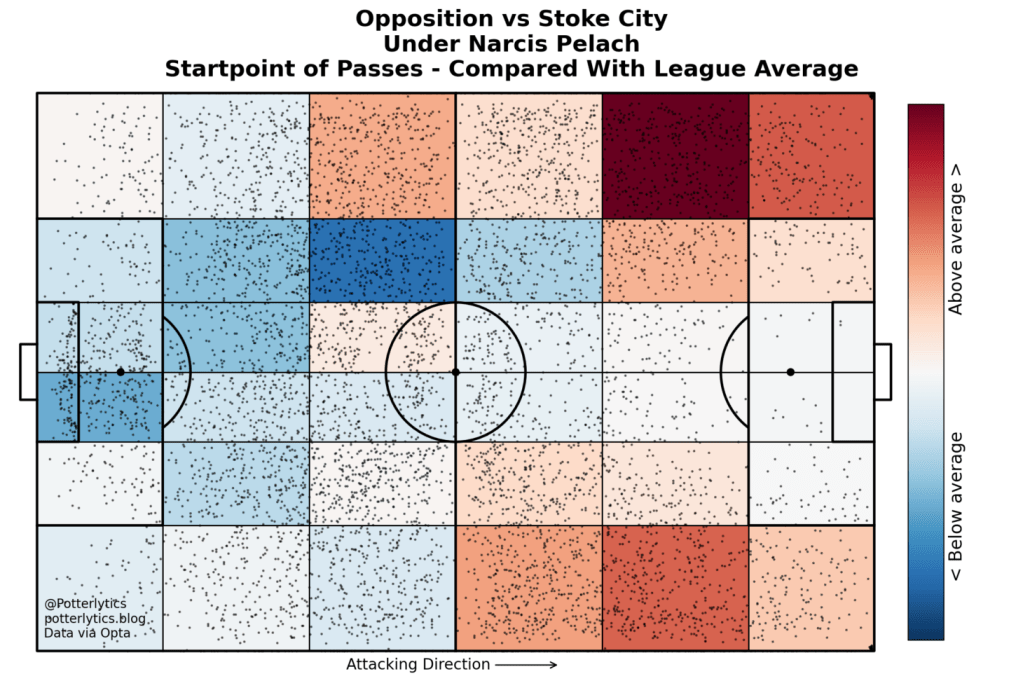

As above, looking at the passes Stoke’s opposition are making, it’s clear that the first line of the defensive press isn’t effective enough at preventing the ball getting into dangerous areas.

Opposition build-up simply plays around Stoke’s compact and narrow lines, and manages to consistently get into dangerous areas wide of the box.

Now, the plan here is for Stoke to simply pack the box full of players and prevent big chances for the opposition. But their unwillingness to press the ball on the edge to prevent crosses, alongside the unwillingness to mark a man moving between spaces in the box, has led to Stoke still conceding above the average xG per shot on average in the division according the Opta.

As shown above, Stoke have not only conceded more shots per game than all teams bar Plymouth Argyle, but the shots they do concede are also higher value, on average, than 14 other teams in the league.

Click each image to zoom in.

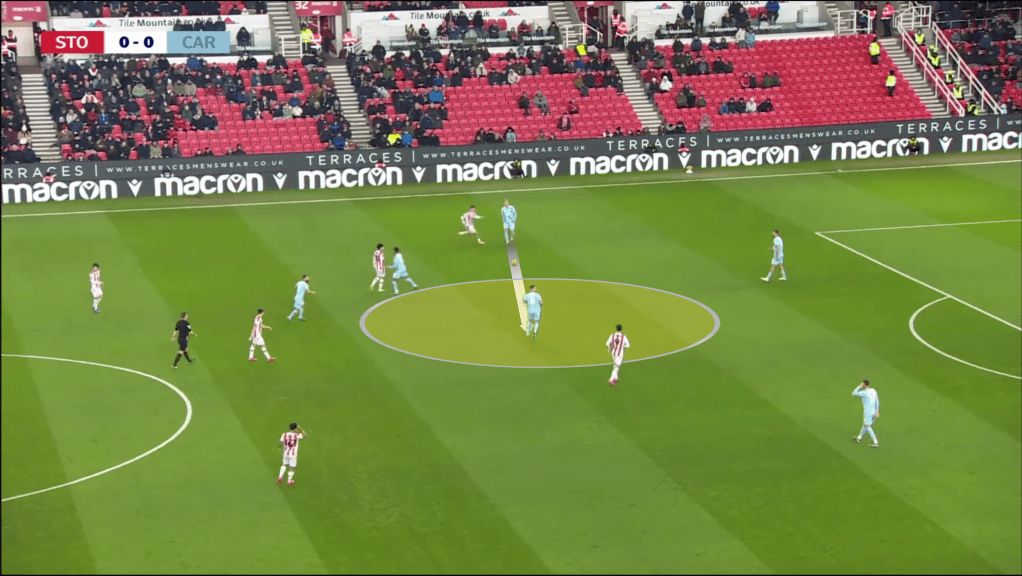

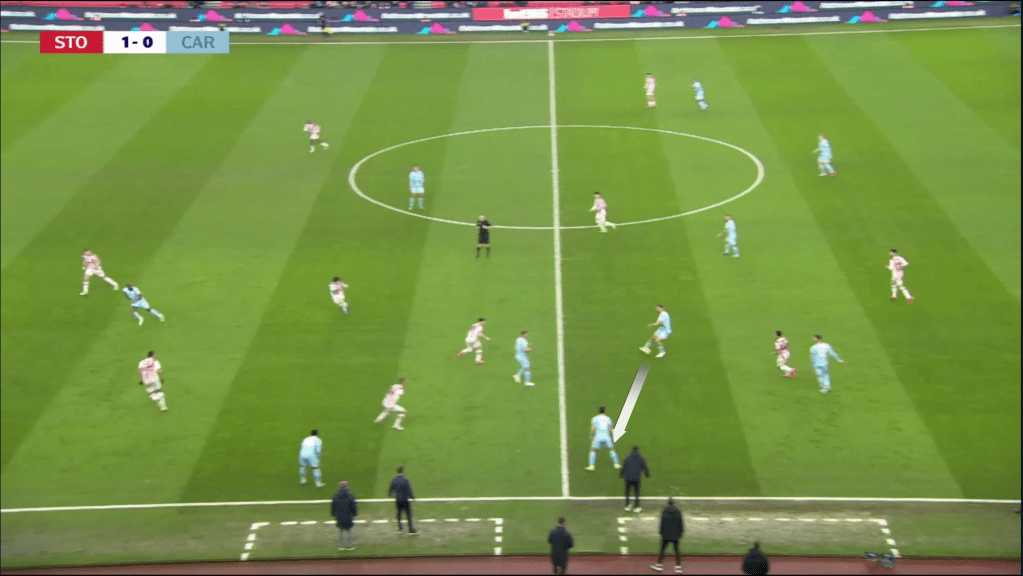

In the above images, from the first half against Cardiff, we see an example of Stoke’s defensive passivity and zonal defensive shape being far too easy to exploit.

As the ball is played out to Cardiff’s right back, Stoke are sat loosely in their 4-4-2 shape, narrow and compact to prevent passes through the centre of the pitch. Koumas presses aggressively towards the player who receives the first pass, and the passer moves forward towards Junho.

But Koumas is pressing alone, and Cardiff play a simple pass into the centre of the pitch to Ralls.

Not a problem, on its own, but because Stoke are so obsessed with keeping their shape and preventing central passes, they give Ralls complete freedom to turn on the ball and pick a pass forward.

And now we see the major issue.

Click each image to zoom in.

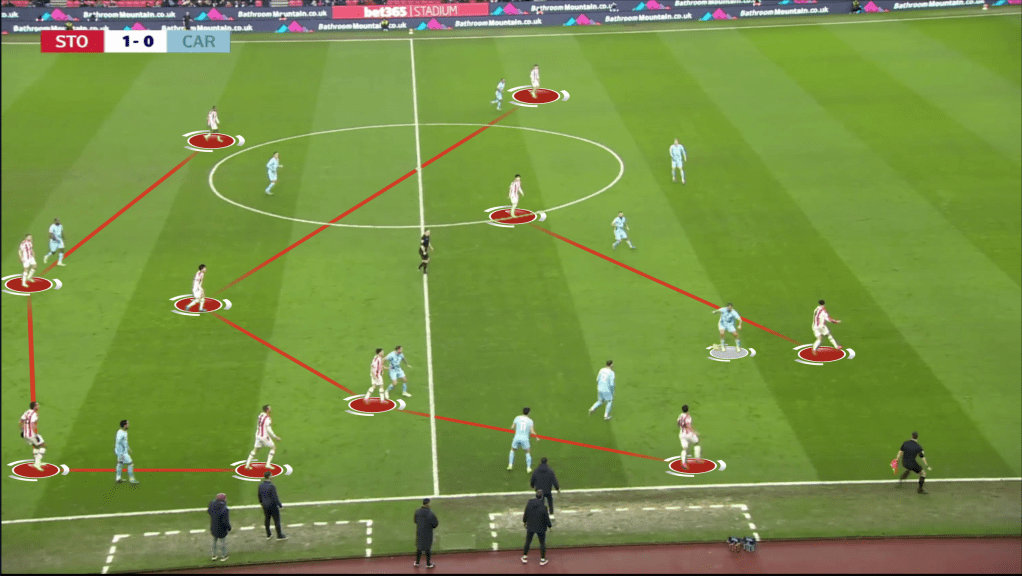

Cardiff do one thing very well in this phase of play – spreading their attacking line to fill the width of the pitch.

Stoke do many things badly, but my biggest problem comes with the lack of recognition of how to prevent attacks like this in their shape and structure.

If you’re sitting as narrow as Stoke are (look at their defence in the left image), and allowing the opposition to have the space wide, you have to be willing to press and compact the space higher up the pitch.

As it stands, Stoke’s forward lines (both midfield and forward lines are disjointed and leaving huge gaps in the middle 3rd in this case) are essentially training cones, with no pressure on the ball at all, allowing a relatively fast break through from Cardiff, and forcing recovery runs of almost 40 yards from their own defenders and midfield.

As the wing back gets the ball, he has 10 yards between himself and Wilmot, and a massive space to drive into with the ball. There’s a 4v4 on Stoke’s back line, and a huge gap in front of them to the recovering Seko and Manhoef.

In the end, the wing back has a very easy time driving into the Stoke box, and as Stoke’s defence recover well to defend the 6 yard box (more on this later), passes to the late arrivers into the area are free, and in the end Johansson’s save keeps the score at 0-0.

With 2 simple passes, Cardiff went from 20 yards in their own half with all 11 Stoke players behind the ball, to a shot from 6 yards inside Stoke’s penalty area from a cutback.

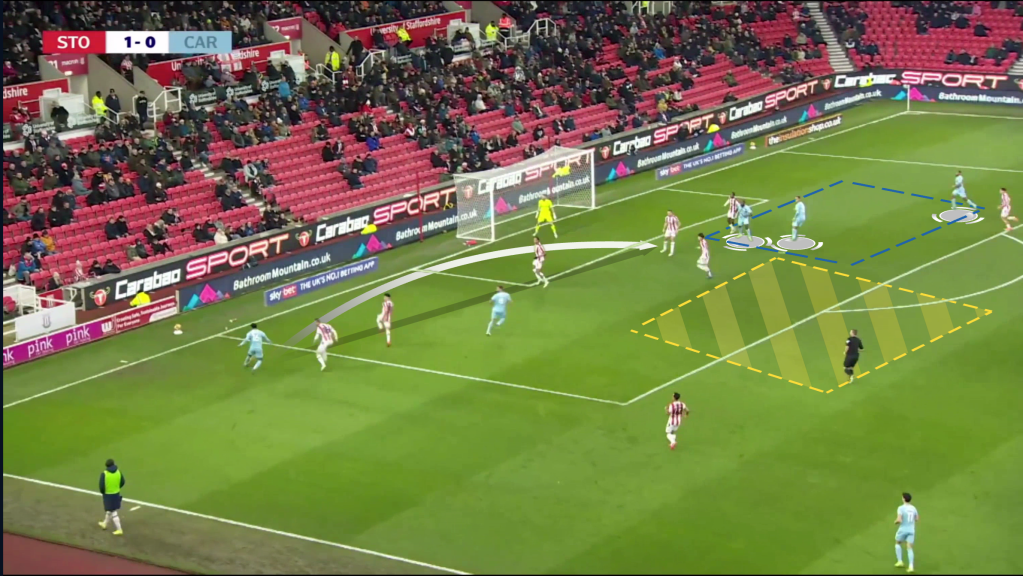

Here we have the build up to Cardiff’s equaliser. Wilmot plays a loose pass to try and slot Cannon through, thinking he’d drop into receive to feet (lol). But as Cardiff win the ball back, Stoke have every player behind the ball apart from Cannon, and all but 2 players on the right hand side of the pitch.

But, as has become common for Stoke this season, the spaces occupied in the defensive shape higher up the pitch are far too easy to get through. Look at the two pictures above, and as the Cardiff player takes the ball forward, he misses a pass inside to the completely free players between Tchamadeu and Junho.

He plays a simple pass wide, which Stoke are in a good position to close out and prevent danger.

But the recognition of where to press, and the ability to press while cutting out passing options, is so poor again.

Wilmot presses aggressively on his own, but the direction of his run blocks off neither the pass down the line nor the pass inside. Moran has, almost inexplicably, dropped off the midfielder to mark an area of space that Seko is already sort-of covering (although he’s also switched left to right about 4 times by this point).

The lack of pressure on the ball, and fundamentally the inability to recognise which spaces are dangerous means Cardiff easily play a pass inside and down the line, and Stoke have turned a 3v3 into a 3v1 in Cardiff’s favour with their positioning.

I believe this focus on defending the spaces leads to confusion in higher areas of the pitch, where players aren’t able to put pressure on the ball and create pressing traps.

Then, as he makes the run down the line, we see another two issues in Stoke’s defensive structure in the low block phase, as every Stoke player watches the ball and defends the centre of the goal.

In the blue dotted area is a 3v1 on Junior Tchamadeu (and the eventual goal comes from a ball deflected to the back post), and in the yellow zone is something we often see with Stoke’s shape, a massive gap on the edge of the penalty area as everyone defends the 6 yard box.

This is the source of the eventual goal, as a cleared header gives someone a free shot 12 yards out. And it happened more than once in the game.

On the left we have the first goal, and on the right we have a similar opportunity that hit the bar. A cross into the box, headed away towards the edge of the box, but every Stoke player is so obsessed with defending the 6 yard box, that they give free shots from 12-18 yards out.

Yes, there are bodies in the way, but I don’t believe these chances – however low value – exist with a more aggressive and less conservative defensive plan in place.

Final 3rd Woes

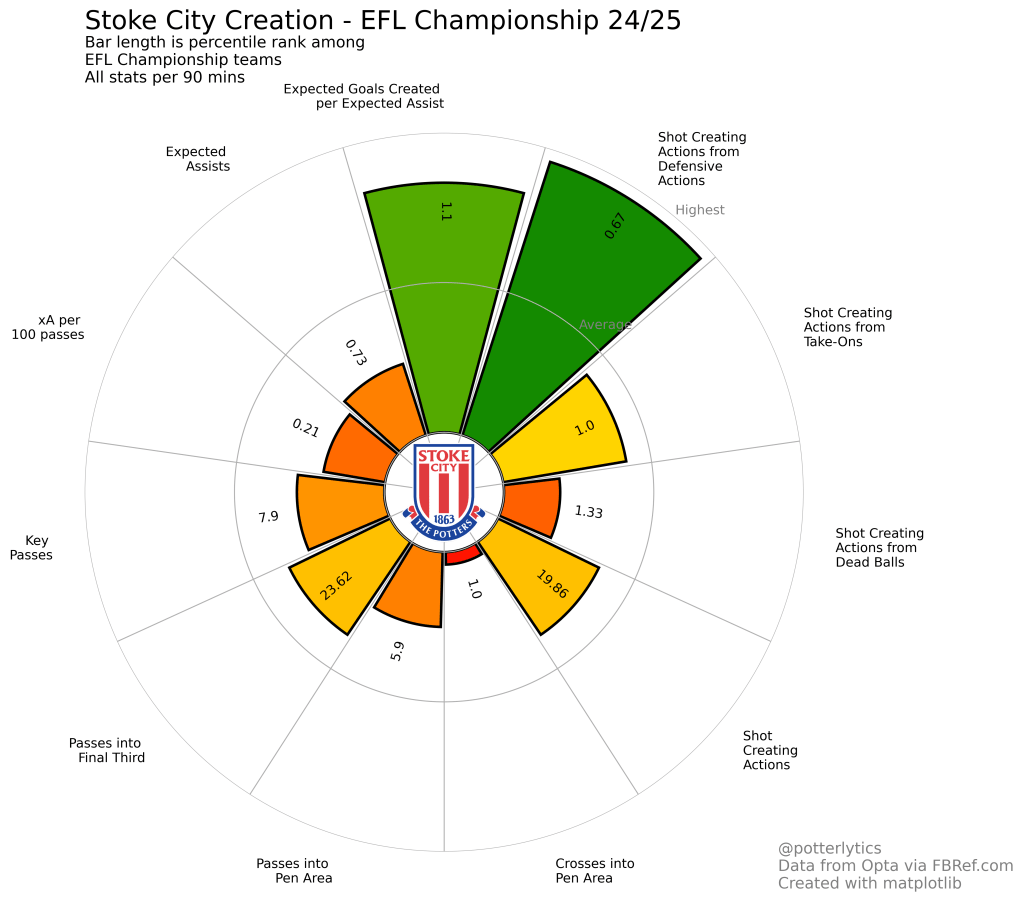

When looking at Stoke’s attacking issues, two big things show up.

Firstly, they’re actually very good at attacking on the break into space. They create the 2nd highest number of shots from defensive actions, and have scored the joint-2nd most goals from fast breaks in the league this season.

But whilst their build up has improved (and I do believe that’s one of few positives from recent performances), the ability to get the ball into the final 3rd and create when they do get it there is so heavily reliant on individual skill, that there are highly variable outcomes.

Their ability to create chances is poor, below average in both getting in the final 3rd and in creating chances in all of the above metrics. Only really excelling in creating big chances from low-value passes – an indication of their ability to be aggressive on the break and drive at defenders.

When playing into space and giving their best players the opportunity to attack, Stoke are dangerous. The much-debated Million Manhoef has produced two exceptional passes into space to assist Lewis Koumas vs Sunderland and Tom Cannon vs Luton.

But when the opposition is set in their defensive shape, Stoke narrow the pitch and stop making runs once the first pass doesn’t come.

The lack of structure in the final 3rd when trying to play the final pass has been a big issue for these young players, and as momentum and confidence tails off, it feels difficult to see much improvement on the horizon. Even for what were our clubs ‘stars’ only a few months ago.

It comes to something when I’m pining for something Alex Neil did, but I really do miss that willingness to set pressing traps and play with a bit more risk.

Alongside it being something I enjoy watching personally, I fully believe it suits the attacking talent we have to be trying to win the ball high up the pitch and break quickly in a structured manner

Yes, we may concede big chances and 1v1s against opponents who can play through us, but we’re already conceding almost 2 xG per game on average by sitting in our own box and allowing opponents who shouldn’t be able to get through to waltz to the penalty area.

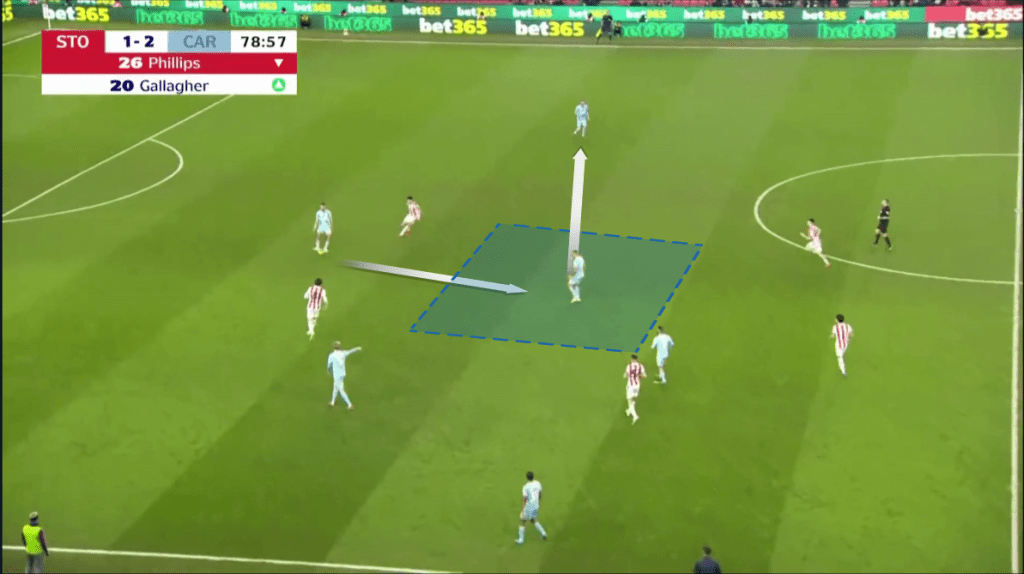

As an example of that poor press, here’s Cardiff keeping the ball with about 10 minutes to go, as Stoke need a goal.

As a preliminary question, I ask – ‘Where are Stoke trying to force the ball in any of these images, and how do they want to win it back?’

Yes, Stoke are chasing the game a little here, so you might expect it to be more disjointed, but in fact this situation appears across the 90 minutes.

On the left image, Cardiff have the ball with one of their centre halves. The two pivots in midfield are more risky passes because of Gallagher’s press, and the midfielder pushing up onto their line. So the ball is played across to the left.

As it’s played, Tom Cannon presses to force the ball central. A good idea, right? But no, because the midfield is 10 yards off the pivot player who receives the ball.

Not only could he turn easily and try to find a forward pass between the (huge) spaces of Stoke’s midfield, but he can simply play the ball out left to the opposite side, where Stoke have no man within 30 yards.

Whilst they can sit in a compact block well, and prevent easy passes centrally, Stoke struggle so much with actively being able to win the ball back in these higher areas against sides with a bit of composure.

The pass out wide is mishit and poorly-weighted from the Cardiff player, which gives Gooch time to press higher. But as he’s had to run full tilt for 30 yards to press, a simple shift of the ball allows another easy pass into the midfielder at the end of the white arrow, who can turn and attack Stoke’s defence directly, because the midfield have pressed on.

Wilmot (spotlighted) is stuck between marking the central player and the wide player, as Seko (the deeper of the midfielders, is 10 yards off.

Every pressing run from a Stoke player ends up having to screen two possible passes, because there doesn’t appear to be a plan to win the ball back aside from ‘don’t let them play centrally’.

As a result, it becomes really easy to drag the shape around with controlled and composed possession, and with it being so compact and narrow, even poorer sides can play around the shape, as Cardiff did in the first example all those paragraphs ago.

A Final Rant About Structure

To finish this off, I have to talk about the club as a whole.

The situation Narcís Pèlach is currently in feels entirely avoidable, and I have such deep sympathy for him in this position.

Having created a brand new club from scratch 6 times since relegation in 2018, it feels like the new Jon Walters era continues where the previous eras left off.

With 1 manager and 2 head coaches in the past 12 months (or just over), 2 technical directors (or sporting directors now), and 2 managers sacked 5 games into a season in the last 4 years, Stoke are grasping around for anything they can to find the answer.

But to me, therein lies the permanent issue with Stoke City as a football club.

There is no ‘answer’ to football.

There’s no such thing as ‘the right’ way of running a club, ‘the best’ head coach, ‘the best’ sporting director, or ‘the best’ signing to make. Football is such a high-variance sport that you can rarely rely simply on ‘good’ to get you into the best position. You need to produce a process and a plan that you think is right for your club, and stick to it until you feel you need to change. From the top to the bottom.

The issue with Stoke has been that, for far too long, they’re a club playing catch-up. From the ‘it’s what Liverpool do’ technical board of Michael O’Neill that lasted 5 games, to Ricky Martin sacking the manager who brought him in, the ideas have almost never lasted more than one or two bad runs of results.

The entirety of Stoke City’s plan for the club hinges on a Fear of Missing Out.

‘What are the ‘good’ clubs doing? Oh Brighton are doing data scouting, let’s get one of them in, but only for a few months because we’ll have a completely different club structure the following summer.’

There’s no issue with learning from what successful clubs are doing, but it’s never done with a depth of understanding of why those ideas are working at those clubs. Stoke take the most surface level idea from an iceberg of a principle that’s worked for other clubs, and then sack it off when it doesn’t immediately turn them into a top 6 side.

The ‘Sporting Director’ role is another example. The use of a sporting director is to provide accountability to the plans and processes that should already be in place for the whole club. They’re not there to control the club in its entirety, because even they rarely last more than 2 seasons.

I was going to put some examples from previous ‘Pre-Season Q&A’ nights still available on YouTube, just for even more depressing memories, but I’m already way over my word limit. If you’re wanting to see how this has unfolded over time, I highly recommend sitting through the ‘plans’ of the last 6 years explained in those chats.

This obsession Stoke have with finding one emperor figure to take control of everything and make it all suddenly click needs to stop, or I fear even medium term success is beyond them.

Sure, maybe we’ll get lucky and roll a 6 in the manager dice roll game, and win a few. But then what happens when they leave, and we have to restructure again? What happens if Walters leaves, either by choice or worse?

I feel for Narcís, he’s going to likely get a January window to bring in players at a club who have only retained only a few players from their squad 18 months ago, and he’s got to learn on the job very quickly, in an environment that has destroyed much more experienced managers than him, at a club that can’t decide what it wants to be.

It’s been crying out for someone to sit down at the highest level of the club, and plan processes and principles for what type of club Stoke City should be. From Men, Academy, and Women’s teams to the catering at the kids’ games. We can’t keep wanting a revolution every 6 months and expecting the same decisions to suddenly bring success because ‘this time we have the right man, honestly’.

Thanks to any and all readers, and please feel free to comment and follow on Twitter at @potterlytics. If you want to hear myself and Lucas Yeomans discussing each Stoke game alongside some exciting interviews, head over to the Cold Wet Tuesday Night Podcast at BBC Sounds.

George