So, there we have it. A 1-0 loss to bottom-of-the-table Sheffield Wednesday the final nail in Alex Neil’s 16 month tenure at Stoke City, and we’re in the market for a manager for the 5th time since relegation.

If you would like a reminder, please do go back and check out the xG article from last year.

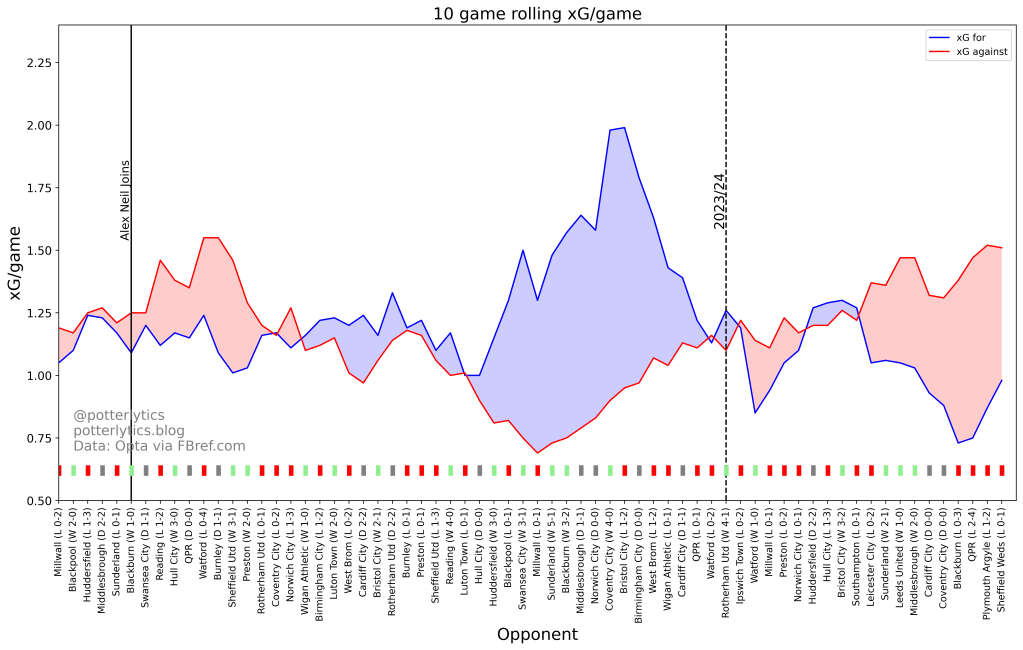

After a shaky start, Neil looked to have turned things around with an incredible run of 12 games or so from February to April 2023. 21 points from a possible 36, including huge wins over Sunderland and Coventry, gave fans hope that things may finally be coming together.

The run was everything Neil had promised. Front-foot, aggressive football, intelligent high pressing, creativity and directness in attack, and most of all: fun. It was something we hadn’t seen since the COVID-hit end to the 19/20 season, and we didn’t even get to experience that in person.

But the good times had to end, and wow, did they come to a brake-slamming emergency stop. A run of 2 points and just 3 goals from 7 games finished off the 22/23 season as the threadbare squad which could rarely rotate struggled to cope with fatigue. Worse still, a back injury to Player of the Season Ben Wilmot compounded the issue in breaking down a deep block.

This was all fairly reasonable in the minds of most, myself included. It was clear that Neil’s plan (at least as it showed itself in March) was a positive one, and one that had given lots of fans a big reason to buy in to a wave of optimism finally surrounding the club. Yes, the run had petered out with a whimper, but there was now a huge chance in the summer for Neil to bring in his own squad almost from scratch. This was a chance that very few managers get, to mould almost the entire club exactly as he wants it.

This was his chance to show us what he wants his team to be…

*Curb Your Enthusiasm Credits Theme*

The season started full of promise. A 4-1 victory over an admittedly poor Rotherham side was a shot in the arm for the fanbase. The new side consisted of 5 debutants and 2 returning loanees, but it was like they’d been playing together for years.

But very quickly there were worrying signs, and a week later Stoke were taken apart in a 2-0 defeat to Ipswich. The ‘all-action’ pressing approach that led to the halcyon run of Feb-April was clearly something that needed more time to develop among these new players. Ipswich were able to bait the press with ease, and play through Stoke as if they weren’t on the same pitch.

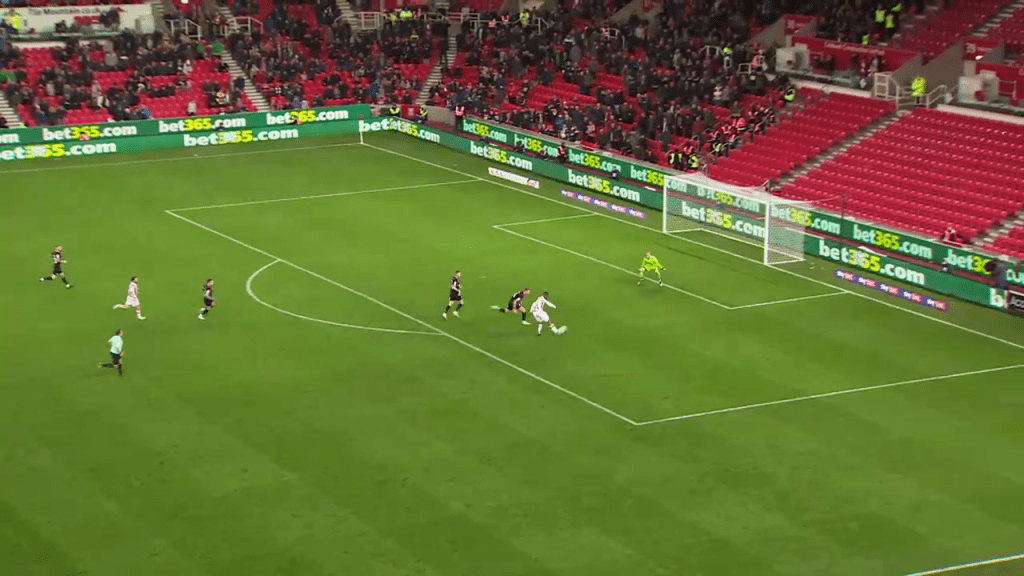

The aptitude of this pressing unit has become a very big issue in the opening 10 games of the season for Stoke, alongside a penchant for allowing attackers to turn in their own box and take a shot. Aside from a battling (and tactically strong) 1-0 win at home to Watford, Stoke were unable to add to their victories column until Gameweek 9, when a late strike from 18 year old Nathan Lowe sealed 3 points away at Bristol City in a very tight, and probably very lucky.

Prior to that game, Stoke were in 20th place, the same position they find themselves 12 games later having removed Neil from office.

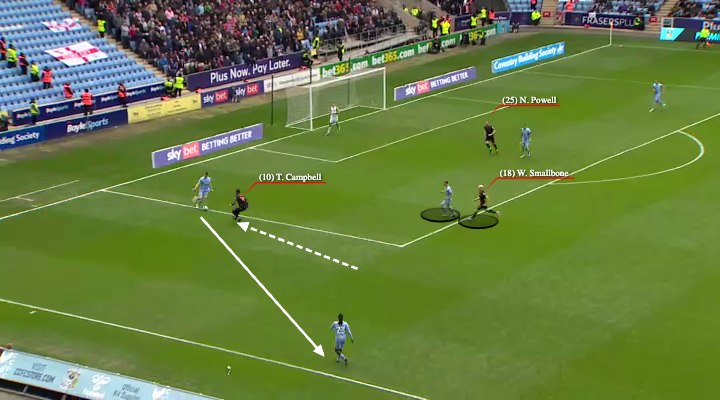

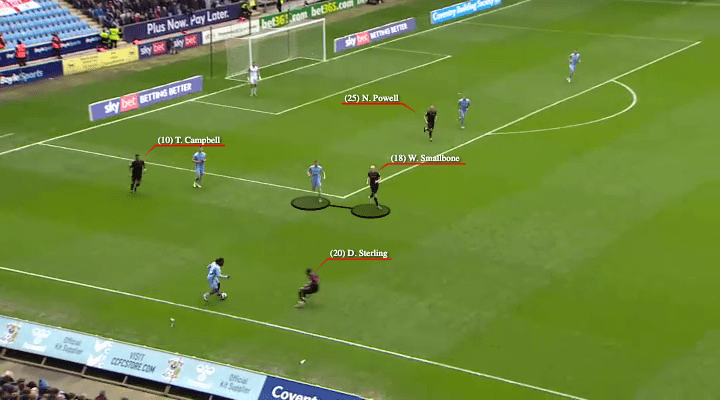

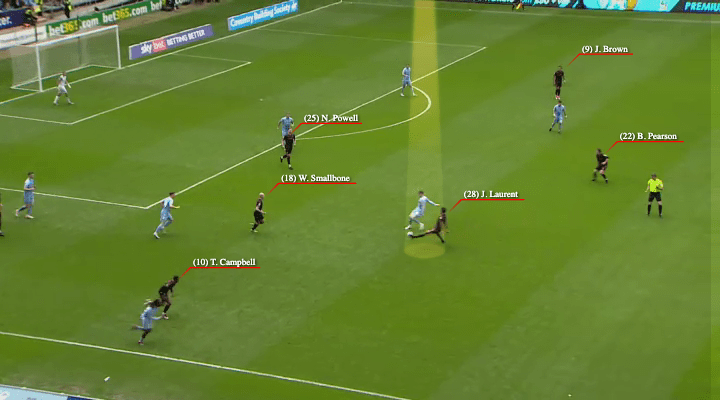

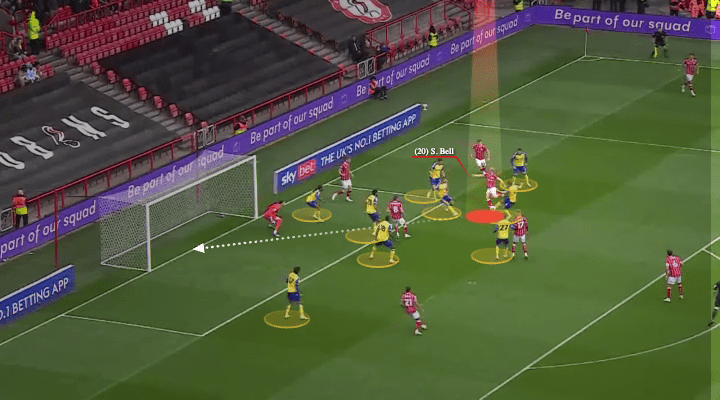

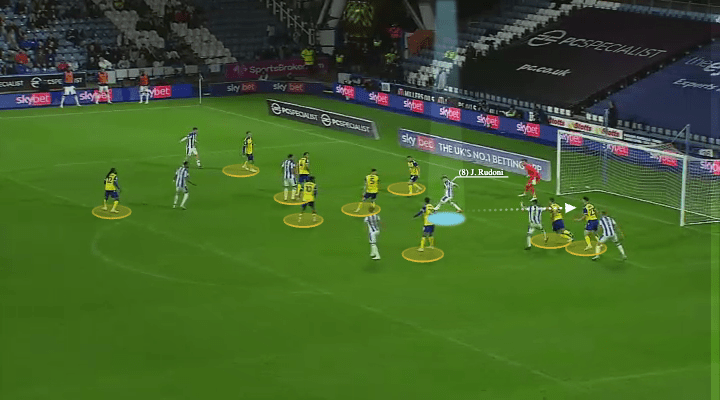

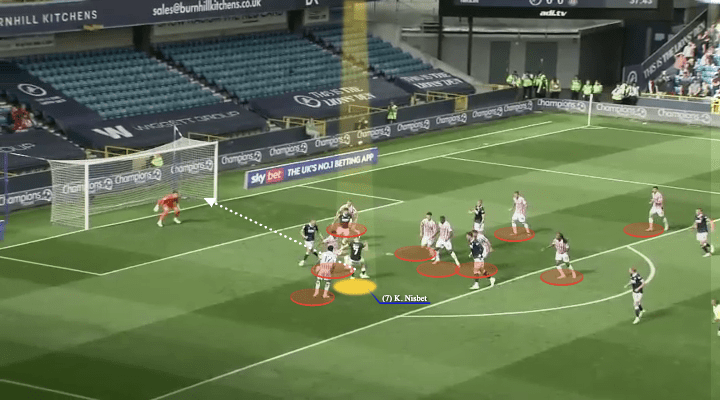

Among these starting few games were the seeds of Neil’s destruction, shown best with the following similar goals conceded by Stoke through that period.

Bottom Left: vs Millwall (A) – Bottom Right: vs Hull (H)

Images: Wyscout

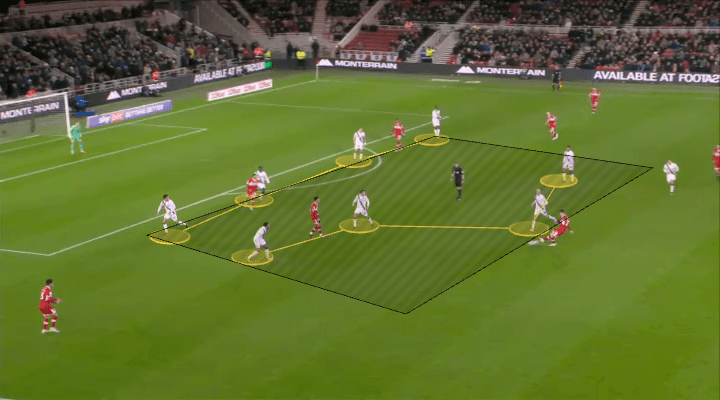

In each of the 4 situations above, the opponent highlighted was able to bring the ball down and get a shot away (all 4 resulted in goals) inside the Stoke area, within the width of the 6 yard box. In each of these cases, stoke had a minimum of 5 players in within 6 yards of the ball as the goalscorer received it.

‘Same old Stoke’, right? Well, yes. And this issue seemed to combine with a run of poor injuries to change Neil’s view on how Stoke needed to add points to their tally in the following weeks.

The ‘Good’ Run

A defensively-strong performance against Southampton saw Stoke go down 1-0 to a glorious free kick, despite a stonewall penalty claim being waved away for the Potters. The blueprint was set, as Stoke looked to pack the midfield and create a scrappy game whereby they might release counterattacks from second balls and hope to defeat other teams in small moments (remember this phrase).

Ignoring the Leicester game, with the many injuries and the embarrassing surrender with 2 banks of 4 stood on their own 6 yard box, Stoke stuck with this ‘crowd them out’ mentality in the midfield throughout the next 10 games, and here began the ‘good run’ which convinced many that the tide was turning.

The 2-1 win at Sunderland was a nervy affair, in which neither team particularly dominated, and neither team particularly deserved to win.

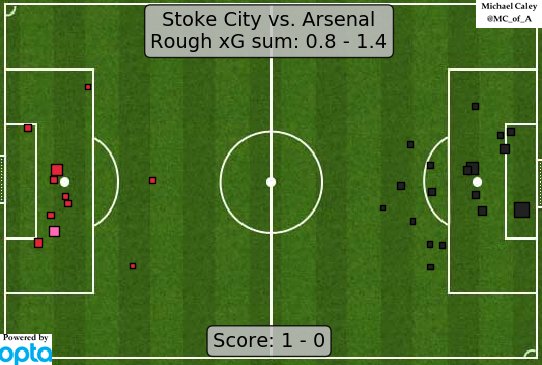

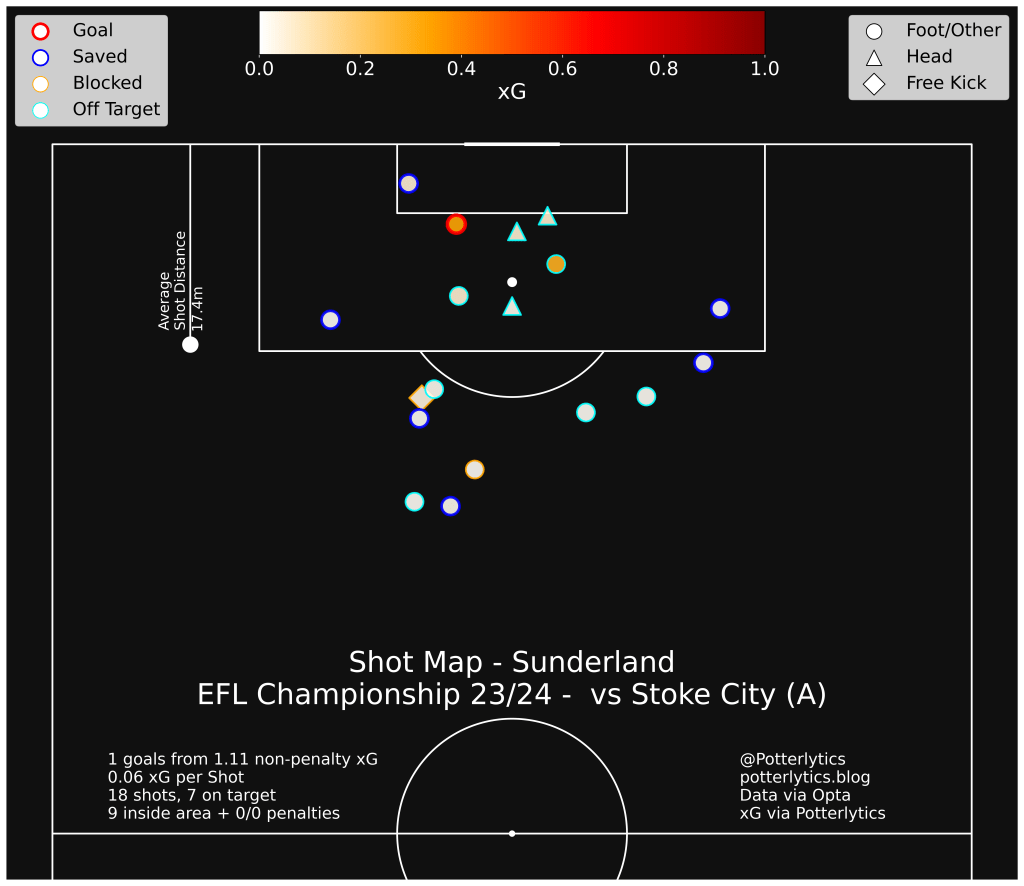

Despite scoring 2 goals, Stoke’s attacking woes continued in the underlying numbers, and from the start of October to the end of November, they amassed only 6.5 xG from 9 games. In only one of those 9 did they achieve above 1 xG in a game, the 2nd dominant performance of the season away at Middlesbrough.

In the same period, despite conceding only 11 goals (4 of those in the final game of November vs QPR), Stoke’s opponents managed to create 13.4 xG, over double Stoke’s tally. It became clear that even though they had managed to pull together 3 wins from 5 unbeaten matches in this time, there was no sustainability to this run of form, unlike the highs of March.

The Middlesborough game was a rare joy. A match in which the press worked perfectly, Stoke’s build up was positive and sharp, and the 2-0 victory was well deserved. Leeds at home brought a rare return to the battling victories of old against higher-level opponents, with players throwing their bodies on the line, and a fantastically jammy set piece own goal bringing home the points. But even this joyous win and genuinely battling performance relied on Leeds missing big chances and a penalty.

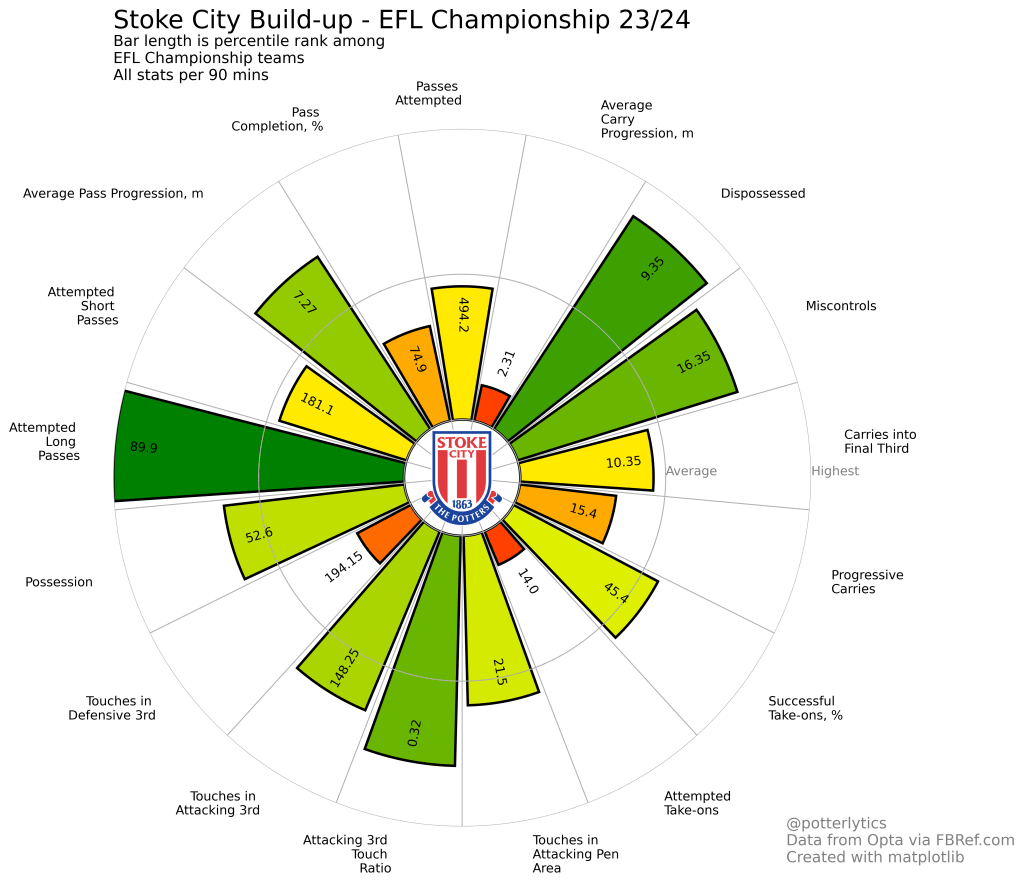

The strength of battling to save points in those 5 unbeaten matches was marked by a scrappy midfield, a lack of creative freedom, and a consistent lack of bodies willing to run ahead of the ball from midfield or in wide areas. The build-up became slower, more laboured, and consistently longer into forward players. At time of writing, Stoke have attempted more long balls than any other team in the league.

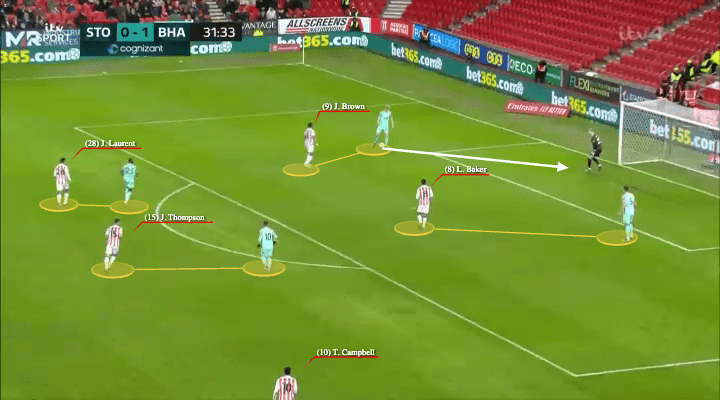

This longer build up was also true of Stoke last season, and reflected the will of Alex Neil to create overloads in the wider areas, which could be hit quickly, either by switches from defence, diagonal passes over the top of fullbacks, or line-breaking passes from centre halves. If all else failed, Jacob Brown (or this season, Mehdi Léris) made a good option for a flick on into a crowded area of the near side midfielder, the full back, and the striker, all ready to win the second ball.

This season, however, the passes into those overloaded areas have been slower to come, less varied, longer, and generally with fewer bodies around the ball.

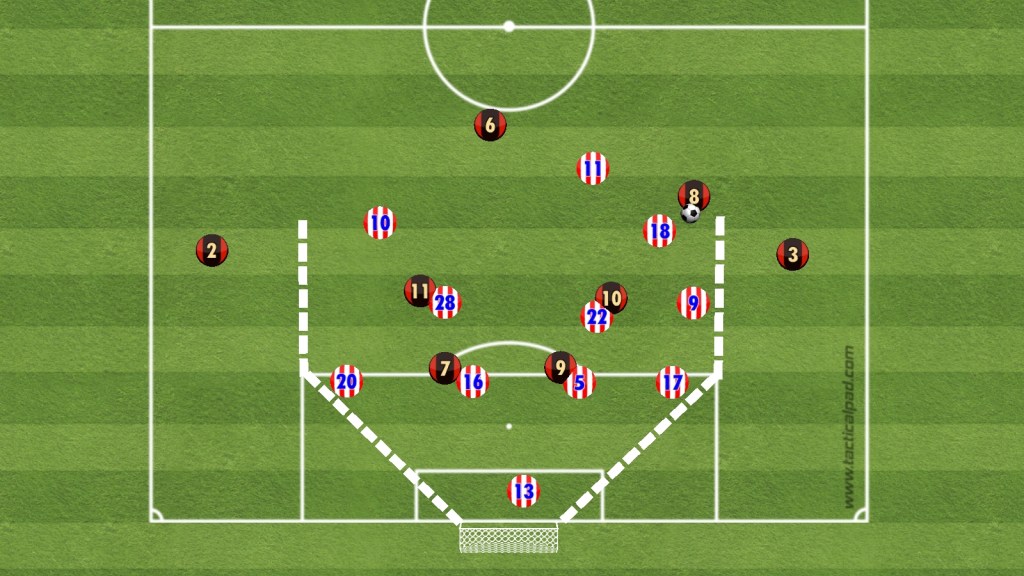

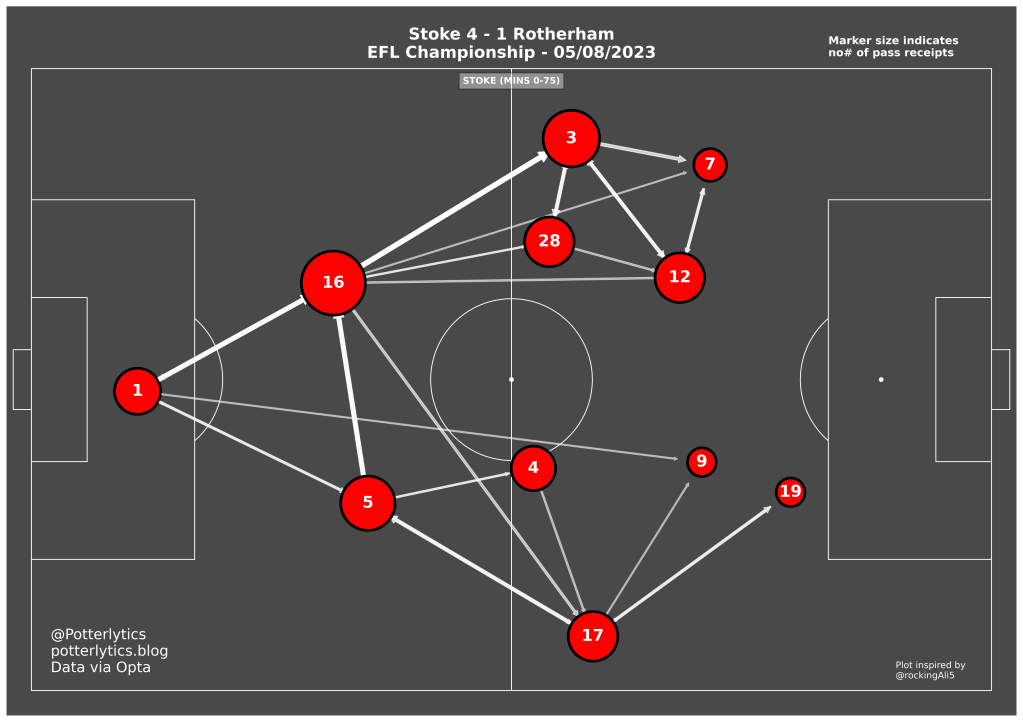

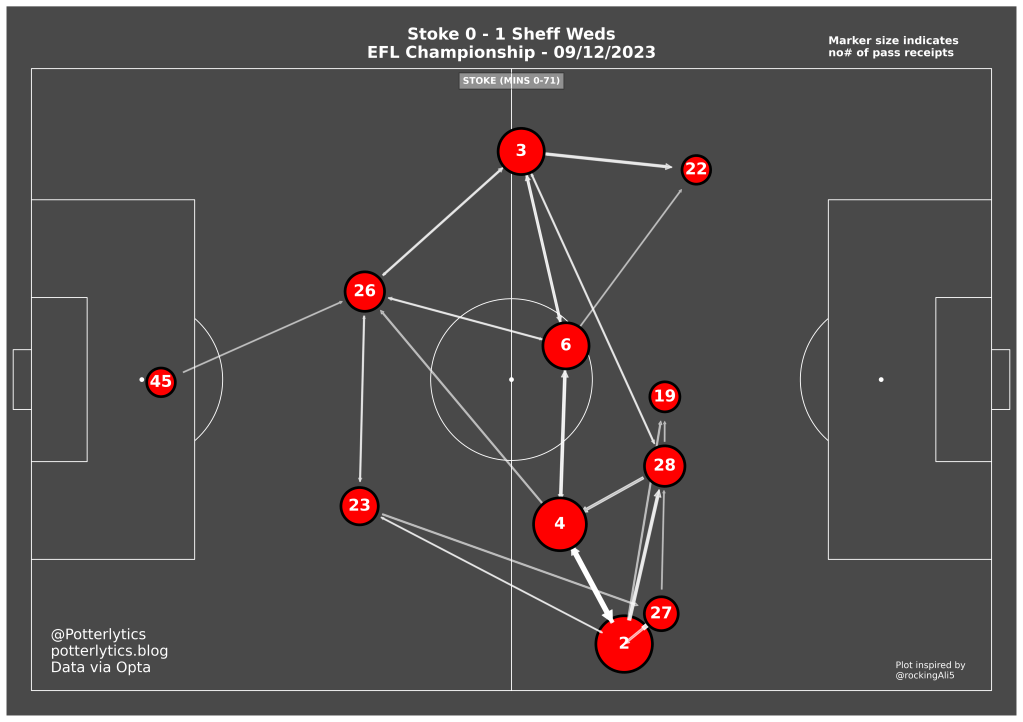

See the difference between the Rotherham game at home, and the Sheffield Wednesday game from Saturday below.

Against Rotherham we see two clear areas, left and right, where players often interlinked to provide overloads. On the left wing we have Stevens pushed high into the opposition half, with Laurent, Johnson and Vidigal connected closely to support progression of the ball. On the right wing, we see Hoever further forward, with Pearson supporting from slightly further away, and Brown/Mmaee pushed higher to run in behind.

The small arrow to Brown from Travers indicated those longer passes as an emergency outlet. Note that in this game both centre backs played a range of progressive passes into midfield and full backs (Wilmot to Hoever in particular was a huge progression route for Stoke).

Against Sheffield Wednesday we see much less cohesion. Both centre backs contributed less to the build up, and more passes went straight down the line to full backs. Gooch and Léris were in similar average positions, and Bae Junho was almost entirely on his own, relying on straight balls down the line from Stevens.

In fact, throughout the season, midfielders have been receiving the ball in deeper and deeper areas as the games have passed.

On average, players in central midfield are receiving the ball ~6 yards deeper in the last 10 games than the first 10. The biggest issue here for me is not necessarily that they’re involved in build-up in deeper areas, that can be fine, but that they’re much less involved in higher areas of the pitch.

Last season we regularly saw Smallbone, Laurent, and Baker pop up in higher areas of the pitch to help create and finish off chances. These last 10 games we’ve not seen nearly as much of that. On the plot, this shows up as the squares around the half spaces near the box, which are much less bright in the second image.

Alongside this, centre midfielders added less xT (I know, I’m sorry, it’s a measure of how useful possession is, but for the purposes of this it basically means their average pass didn’t move the ball as close to the goal as it did before) in their passes in the last 10 games.

The same is seen in the passes made by our centre backs. In the second plot, we see that fewer passes make it into half spaces across the halfway line, and far fewer make it into the central areas just inside Stoke’s half. The indication here is that Stoke’s build-up is much less likely to break the initial line of the opposition press by playing into the midfield than it was early in the season.

All this supports the thesis of Neil struggling to fix the defensive issues of the early season, and as such he tried to step away from his centre backs playing into more risky areas, instead preferring to allow centre midfielders to drop deeper than the opposition press, and hoping the real creativity would come from quick breaks or high regains.

‘Front-Foot, Aggressive Football’?

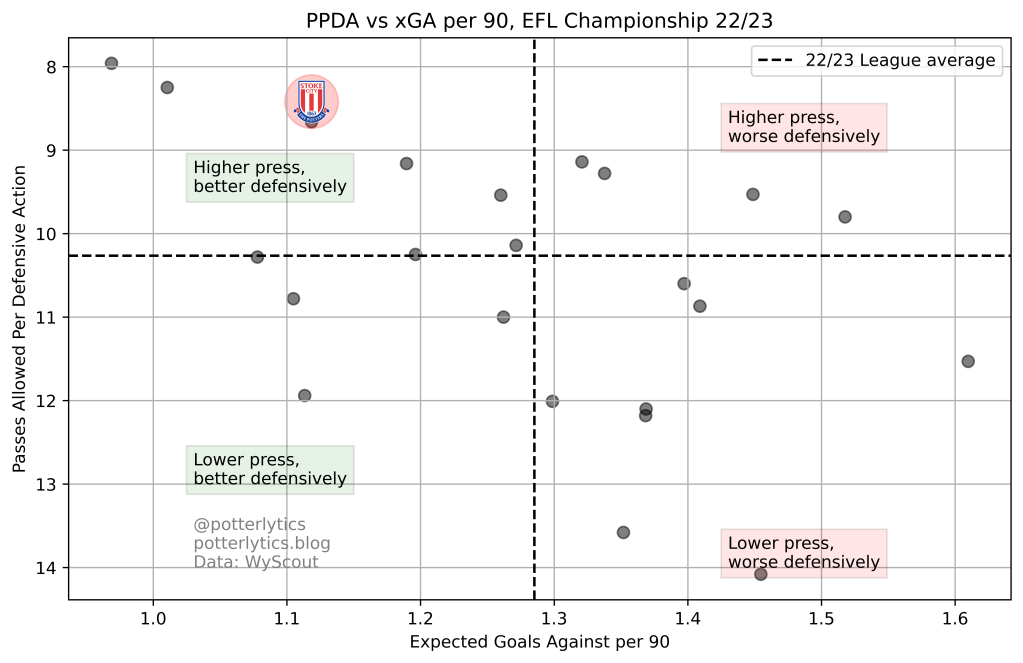

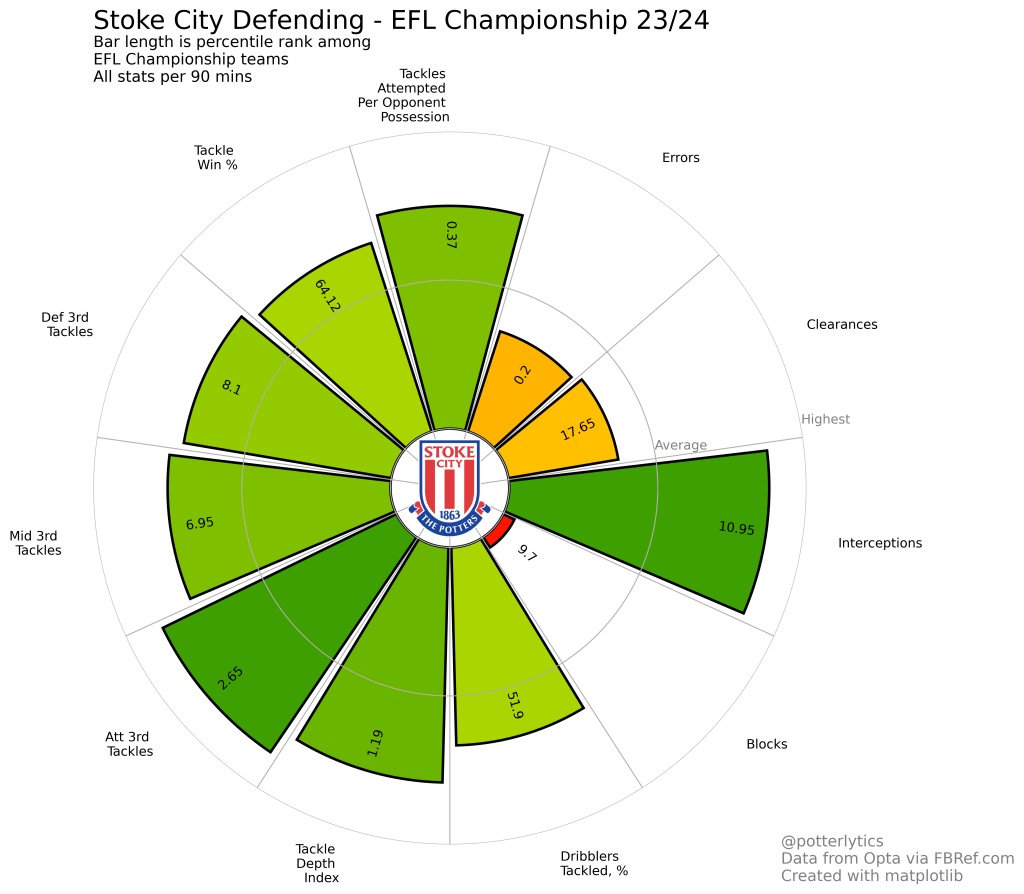

Stoke’s high press has actually been pretty good this season, and they’re still one of the most aggressive pressers in the league. Stoke’s PPDA (how many passes they allow the opponent to make before making a tackle/interception etc) of 8.98 is the lowest (i.e. the most aggressive press) in the league. They make the 5th most attacking 3rd tackles of any side, and have the highest duels, tackles and interceptions per minute of opponent possession.

We can see this in the two radars below.

In the left-hand radar, we see that Stoke make lots of tackles and interceptions, lots of tackles high up the pitch, and a larger-than-average portion of their tackles are high up the pitch.

Similarly, in the right-hand radar, we see that opponents playing against Stoke have few touches in the attacking 3rd, a very low pass completion, and a lower-than-average attacking 3rd touch ratio (number of touches in attacking third/total number of touches).

Stoke are still good at pressing, although their numbers have fallen a little in the last few weeks.

Despite this, Stoke have yet to score a goal from a high turnover all season. From 124 of these occurrences (2nd only to Leeds), 28 have ended in a shot, the 5th highest number in the league. The lack of a true goalscoring threat from this key part of Alex Neil’s ethos has further compounded the attacking woes, and couldn’t cover up the defensive errors as well as they had earlier in the season.

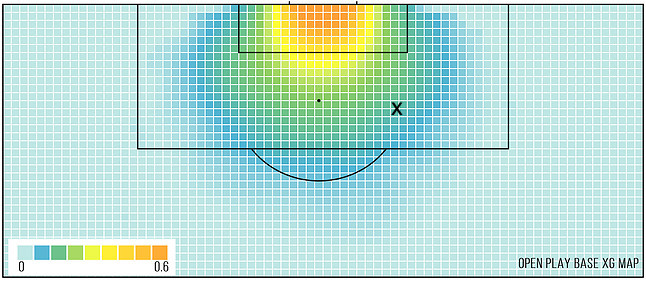

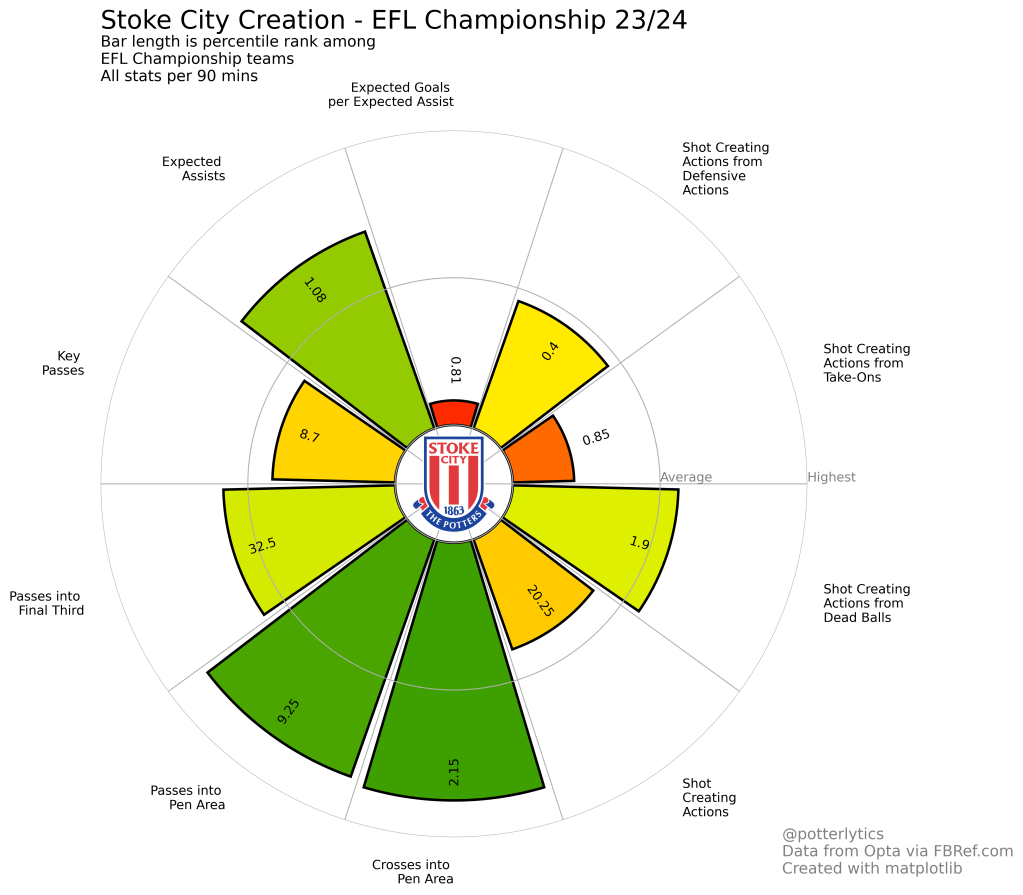

The creativity they do have comes often from throwing the ball into the box and hoping to pick up the resulting pinball. They put far more crosses than average into the box, and pass the ball into the area more than average too. But from this relatively high ‘expected assist’ value (how likely a pass is to result in a goal from 0-1) comes a very low conversion into xG. The xG per xA section of the radar shows that Stoke are among the poorest at the league in turning balls into good areas into high value chances.

There are two possible issues that can cause this, and I think Stoke fall foul of both, but more likely the overriding issue is the latter of the following problems.

Firstly, your shooting players could be poor at getting into those good positions, or poor at turning good passes and crosses into shots. Secondly, but more pertinent for Stoke in my opinion, you can be putting a high volume of low-value balls into the box, inflating your expected assists value but converting very few of these deliveries into good chances. This is supported by the high number of crosses and passes into the box, and an xA value that, despite being above average, is still lower in league rank than the volume of balls into the box.

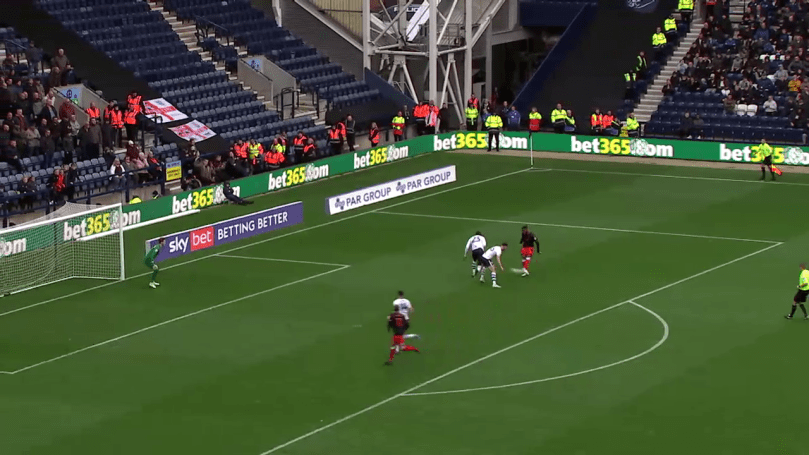

Crosses are a pretty low-efficiency way of scoring goals, and that becomes even more inefficient when you don’t have lots of bodies in the box as in Stoke’s last 10 games. Compare this to the high value chances created by cut backs in March’s run, and we see a huge difference in the efficiency of Stoke’s attacks.

‘The Malaise Is Deep’

Thanks to John Percy for that turn of phrase. It really does describe the club perfectly.

Although Neil can point to several games where Stoke were on the wrong end of little mistakes, his classic line of ‘we just need to be on top in those moments’ still rings in the ears of every Stoke fan who could stand the post-match press conferences after a loss.

But at some point, you have to look into why so many of these games have been decided by small moments. The Championship is a very scrappy league, with games often decided by tiny margins, but the issue with Alex Neil’s 23/24 Stoke side is that they forced games to be this way in the last 10 weeks or so.

It’s seen perfectly in the Sheffield Wednesday game. Yes, Stoke should’ve scored a (very dubious) penalty. Mmaee and Junho Bae probably should’ve scored big chances too, but Sheffield Wednesday were given a chance to win with Stoke’s lack of control on the ball and unwillingness to play through the lines.

The scrappy nature of the match, enforced by a lack of confidence on the ball, a lack of sharpness in passing, and a midfield 3 tasked with battling their way through the game, was the reason that moment existed for the opposition.

Even the games in which Neil appeared to make attacking changes, namely vs QPR and Plymouth in which a front 4 of Vidigal, Mmaee, Campbell and Junho started, appeared more out of desperation to stop the attacking rot than a true plan.

The front 4 did create more chances against these two defensively weak opponents, despite often appearing to be left to their own devices in terms of how to break down the opposition. But even this relatively conservative attempt to let some technical players do some attacking immediately led the return of defensive woes, with the team conceding 4 (from > 2 xG) to a QPR side that had only scored 12 goals all season by that point.

And So It Begins… Again… Again…

And here you find us again, returning to the managerial market, like an addict trying to find that one hit of dopamine that will make everything great again.

I’ve been clear in my views before about the model of the club, and it will be very interesting to see if the de-facto ‘long term dudes’, in Ricky Martin and Jared Dublin, will survive contact with the next manager who walks through the door. Martin made it clear in the summer that the aim was for Stoke to build with a core ethos of ‘high tempo, aggressive, front-foot football’ in the mould of February to April’s run of form. It was even more clear that there was very little consideration that Alex Neil might not be able to deliver that.

Given the previous willingness of the owners to allow a manager to tear up the foundations of the club as soon as they are announced, any new boss may be likely to have a veto on pretty much anyone in the club. It may depend how much of Ricky Martin’s spiel has been bought into by John Coates, but the dice gets rolled again, and maybe this time we’ll get lucky…

My last post on here ended with a genuine ‘Bravo, Alex’ after the Watford win.

This one will end with a slightly more sarcastic line.

Bravo, John.

Thanks to any and all readers, and please feel free to comment and follow on Twitter at @potterlytics.

Should you wish to donate to help with the running costs of the site, and the data subscriptions we use, please feel free to visit our donations page here. Any and all help is very much appreciated!

George