Well, it’s been a couple of months since my last written piece, so I guess I should check in on how Stoke are doing- oh. Wow. Erm. S***.

It really wasn’t fun watching Stoke’s latest attempt to shoot their own feet off in the Welsh capital, and it doesn’t help that it was a tale we’ve all read before.

A slow start, a couple of cheap goals gifted to the opposition, a second half with some huffing and puffing but no real end product, and yet another match where the manager is left bemoaning defensive frailties and poor finishing.

But why? What’s wrong with us? Why can’t we just be normal?

Here are a few of my main takeaways from the game which dropped Stoke into the bottom 3 for the first time since the first lockdown, in that long-forgotten summer of 2020.

Panic! In The Penalty Box

Starting off defensively, we’ve seen the return of a long-maligned aspect of Stoke’s past 6 years in the Championship over the past few weeks, as defensive frailties in small moments of the match inevitably lead to opposition goals.

The first goal came from a set piece during a period of Cardiff dominance, and the second came after a similar period of Stoke dominance, and this defensive frailty has plagued the team consistently under several managers now.

From Steven Schumacher’s 12 league games so far, Stoke have conceded 18 goals in total. In 7 of these 12 games, they’ve conceded the first goal, coming back to gain just 1 point from those 7 matches in the away game vs Watford.

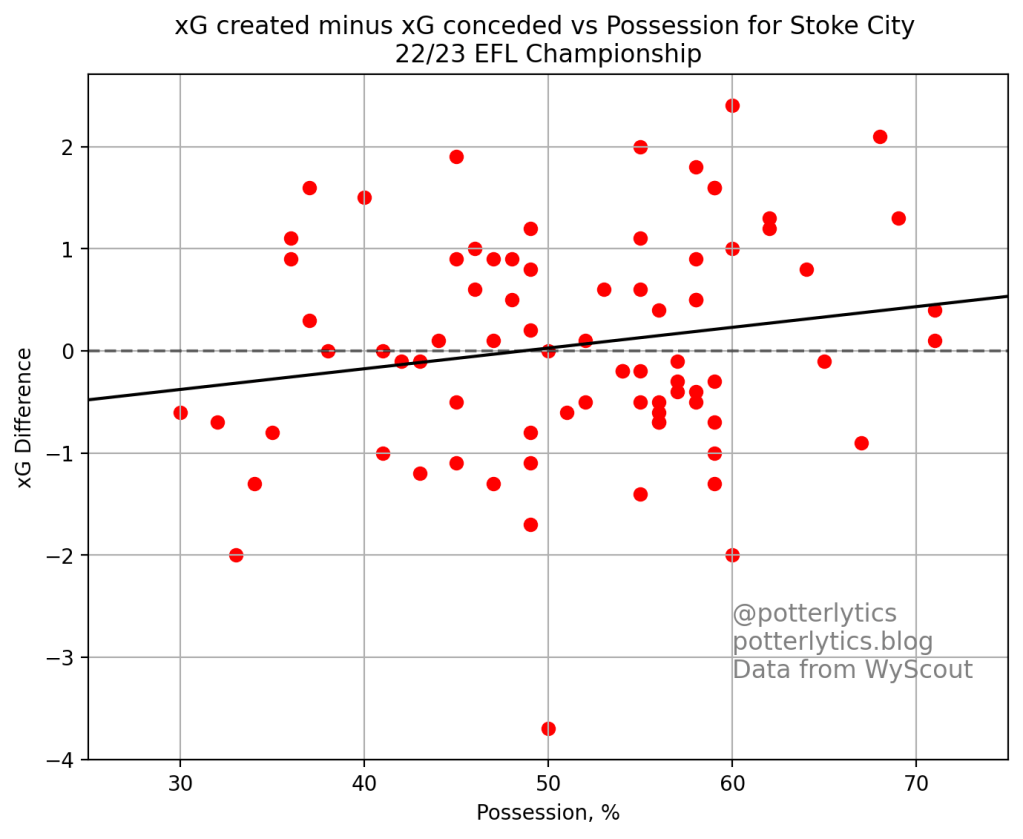

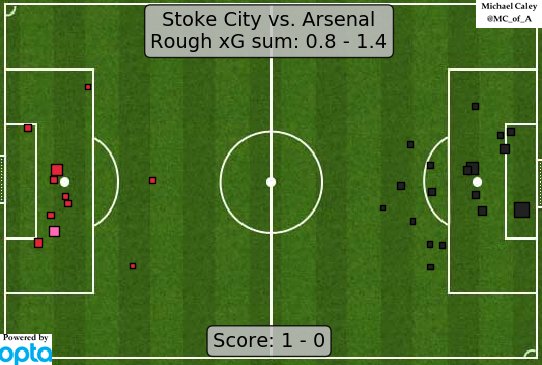

But strangely enough, Stoke are actually looking okay in some of their defensive underlying numbers. They’re well below the average in terms of the number of times they allow the opposition into their defensive 3rd, and similarly below the average in the number of times opponents get into their penalty area. Pretty good? Right?

Given that we’ve played Leicester, Ipswich, and Coventry in that time, that certainly looks okay at a glance. But as always, stats need context and depth, and some of you may already be shouting at the screen in anger.

“We Lost It In Those Small Moments” – Ancient Proverb, Unknown Stoke City Managers circa 2018-2024.

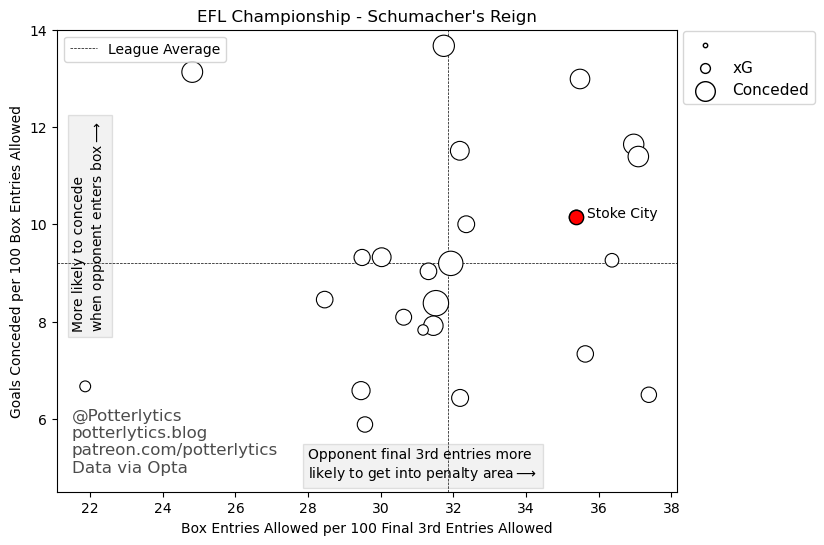

Whilst Stoke appear good at stopping opponents getting into the box and final third, when we look at a slightly different aspect of their defending, we see the issue.

The plot above shows us, in my opinion, part of the reason Stoke are managing to concede so many in recent games. Two major things are noticeable.

Firstly, when an opponent gets into the final 3rd against Stoke, they’re much more likely than average to continue into the penalty area.

Secondly, once an opponent gets into Stoke’s penalty area, they are more likely than average to score a goal, despite Stoke conceding a relatively low xG (See my xG explainer here).

Part of this is explained by the fact Stoke often concede early, so opponents don’t need to push forwards as much or try to create chances, but it also showcases the frailty in the defence that means opponents are gifted those early goals.

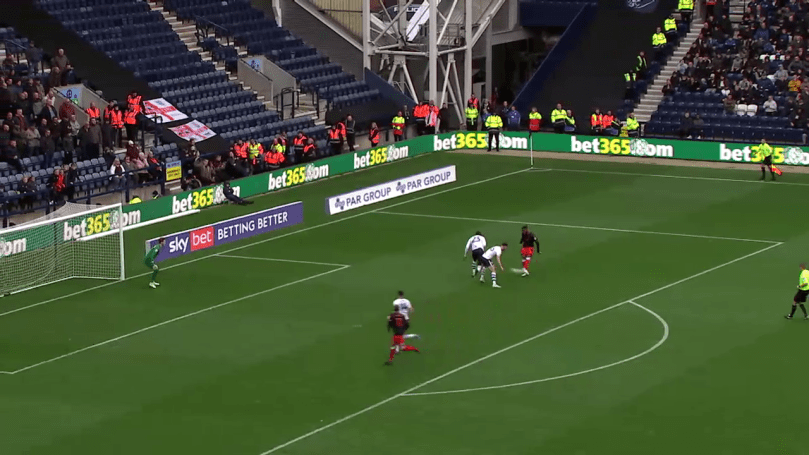

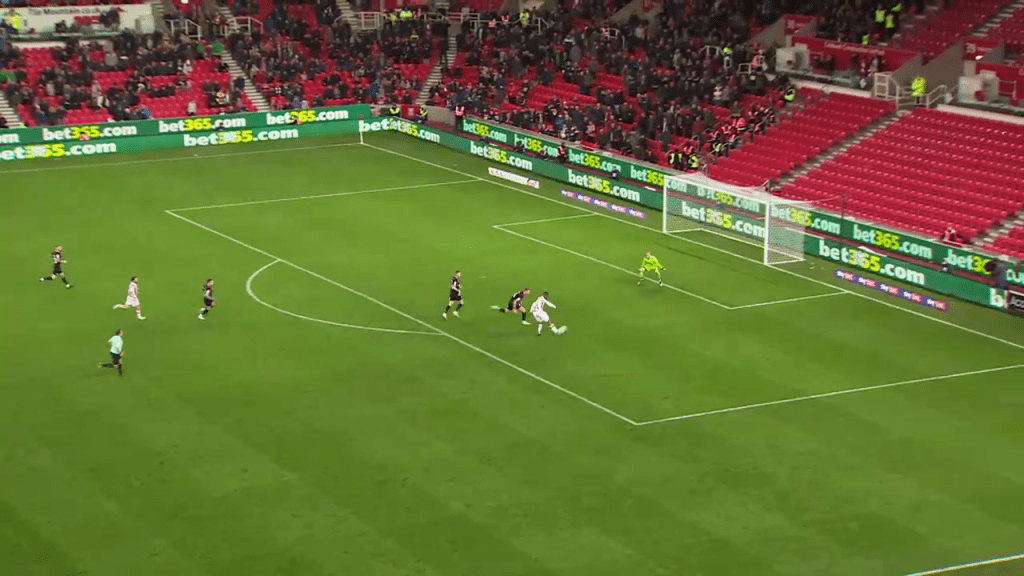

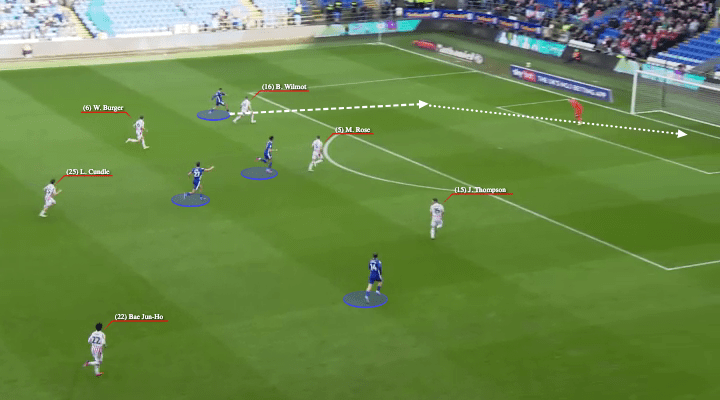

Let’s take a look at the second goal vs Cardiff as an example.

Talk about the fact we can’t recognise danger, despite a several second scrap no-one gets back and they’re 4v3.

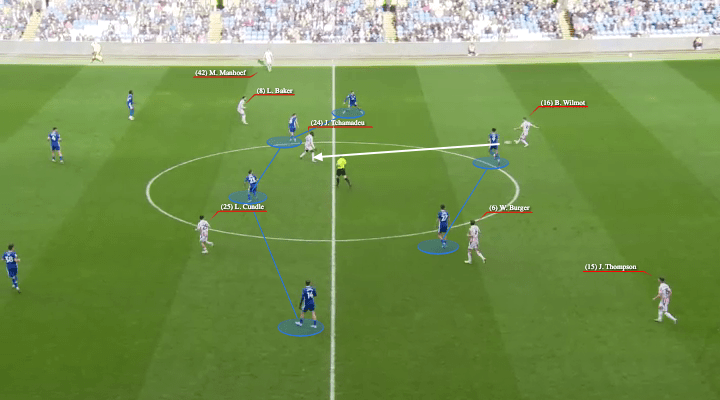

First up, this is a pretty standard piece of play. Tchamadeu has come into the number 6 role to receive the ball, and there is a line of 4 ahead of him in Bae, Cundle, Baker and Manhoef, with Ennis on the back line. This is a really good thing for Schumacher’s plan, Tchamadeu is free and there are Stoke players in between Cardiff’s pressing lines.

But then, disaster. Tchamadeu’s touch isn’t quite right, and he’s pressed well by Cardiff. He retreats and tries to play the bouncing ball back to a defender, but it never quite sits for him to play it cleanly.

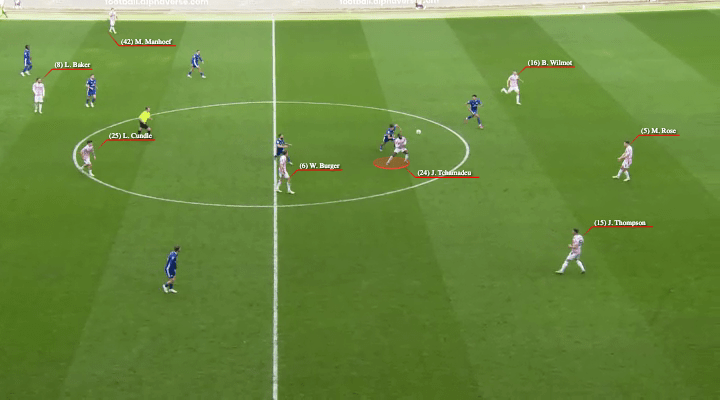

In the 7 seconds between the first and second images, a scrap is taking place. Burger comes in to help, and Cundle drops towards the melee. All the while, Bowler and Grant push forward for Cardiff, sensing that there may be a big chance here should the ball pop out in their favour. The midfielder closest to Baker moves up to become a passing option, and the ball gets to him.

Within two unopposed straight passes of a 10-second 50/50 scrap around the centre circle, Cardiff are in on goal with a 4v3. Burger, Cundle and Bae are dropping to help, but realistically only Wilmot, Rose and Thompson are in position to stop the attack unless Grant slows the play down.

Wilmot shepherds Grant well down the wide area, and forces a left footed shot, but still at this point he has the option of shooting, playing across goal, or pulling back to the Cardiff player on the edge of the box.

From image 1 to a goal within 3 passes. 10 seconds of play where Stoke’s midfield were watching and waiting, rather than dropping behind the ball ready to help the defence.

I’m being slightly harsh there, as you wouldn’t expect everyone to immediately drop behind the ball, and the shot will disappoint Iversen, who is currently underperforming his Post-Shot xG numbers by a goal every other game, but this is a goal that is inherently Stoke-like.

Midfielders slow to recognise the danger, recovering slowly both in behind the ball when it’s in the 50/50, and even slower when the ball is going towards the box, and a shot from a low-value position against a set goalkeeper still somehow finding its way into the goal.

Specifically looking at the slow recovery of midfielders, my instinct is to consider the fluidity of the midfield out of possession in comparison with Alex Neil, whereby it was clear that, on losing the ball, we’d pretty much always have a Ben Pearson (or Thompson) sat deep and waiting to clear up. Schumacher’s flexible system in which players have to fill in for others when they move between positions, means that players themselves have to take the reins and recognise when there is danger to defend and spaces to cover, as opposed to the set positioning of our old friend the Football Understanderer™.

Small moments are still crucial in these losses, and this kind of slow recovery and a lack of recognition of danger has been consistent in the past 5 weeks or so of poor performances. When we give the opponents a chance in those infamous ‘moments’, we tend to give them a goal out of nothing.

‘The Same Thing We Do Every Game, Pinky’

And then we move to the other end of the pitch, where a different type of problem has arisen.

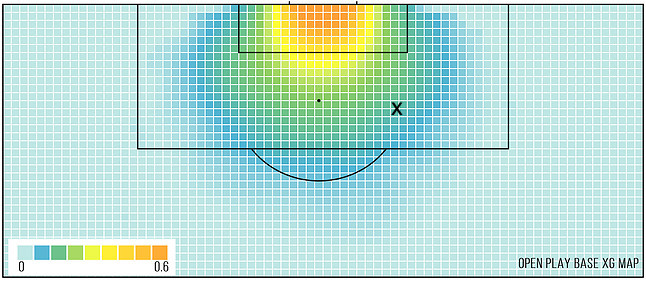

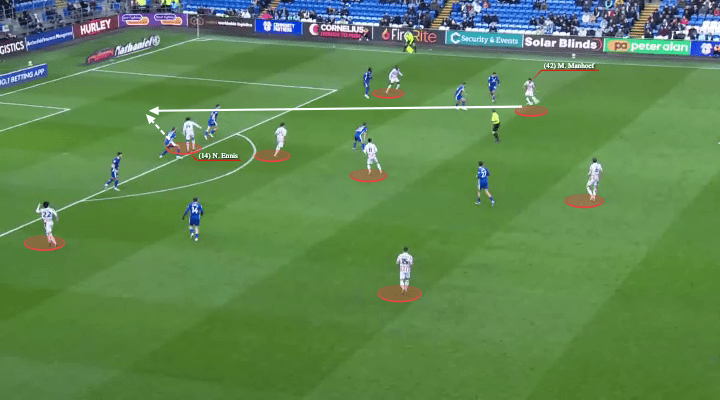

Despite the huge chance scored by Bae Jun-ho, it was 2 other chances that were most positive for me, both falling to new signing Niall Ennis. Both chances were the result of positive play from Stoke, and from quality passes breaking the lines and getting the ball into good areas from our wingers, Manhoef and Bae Junho.

The reason I took notice of these two chances in particular is that they represent a very different style of chance from the majority of play in our last few weeks of football.

I mean, what a bloody ball that is, right?

Manhoef comes inside and we see Stoke’s fluid setup working perfectly. There are so many options available to Manhoef as he beats his man. Tchamadeu moves wider into the space on the right, Lewis Baker backs off into space between midfielders, Cundle is moving into the half space on the inside right, and Junho is making a run outside his fullback for the raking diagonal.

All of that movement means Manhoef can show a moment of immense quality and vision, see Niall Ennis’ run between two centre halves, and play a perfectly-weighted ball into the space which Ennis couldn’t quite finish.

We see a very different, but still very positive, piece of play here from Burger, Junho and Ennis.

Burger receives the ball in a tight space, and plays it into an area behind the fullback. Junho is aware of this space and makes the run, while Ennis gets into the box. Bae pulls the ball back and Ennis is waiting to pounce, forcing a save from the Cardiff keeper.

Whilst these two may seem like innocuous pieces of play, or further evidence of our poor finishing, I think these chances represent something we’ve been doing very little of recently, which is creating high-value open play chances using our fluidity and quality on the ball.

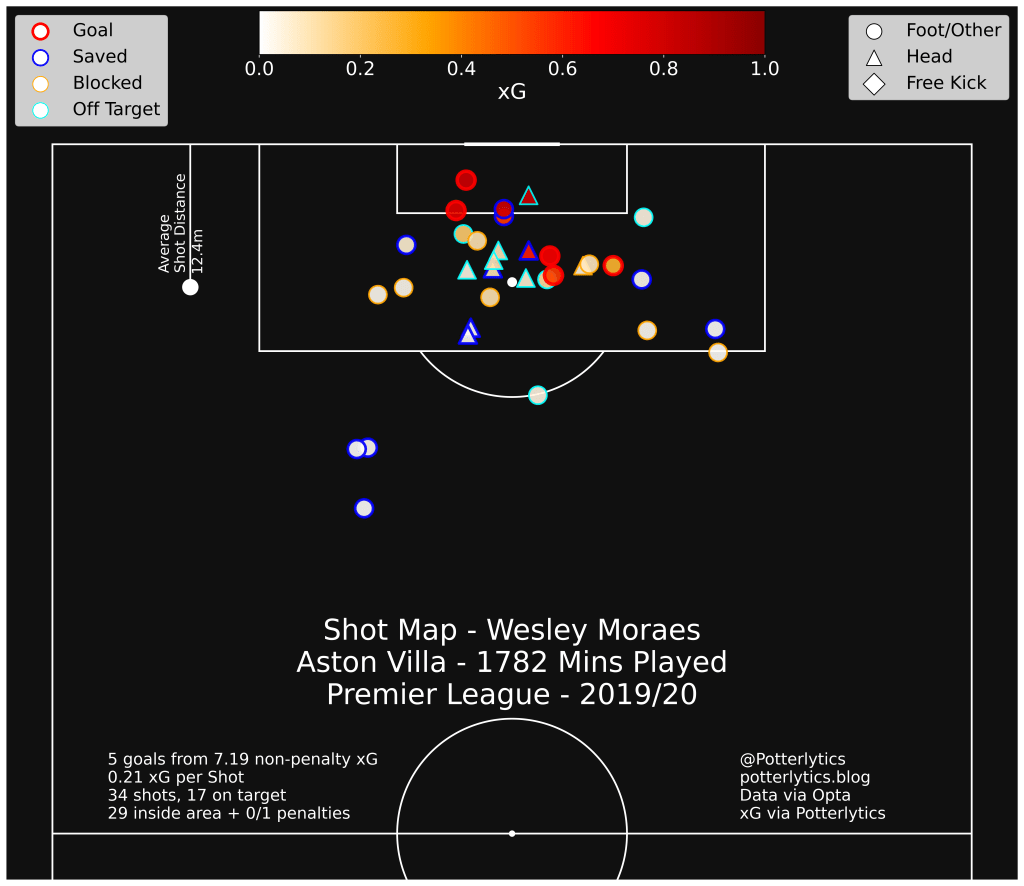

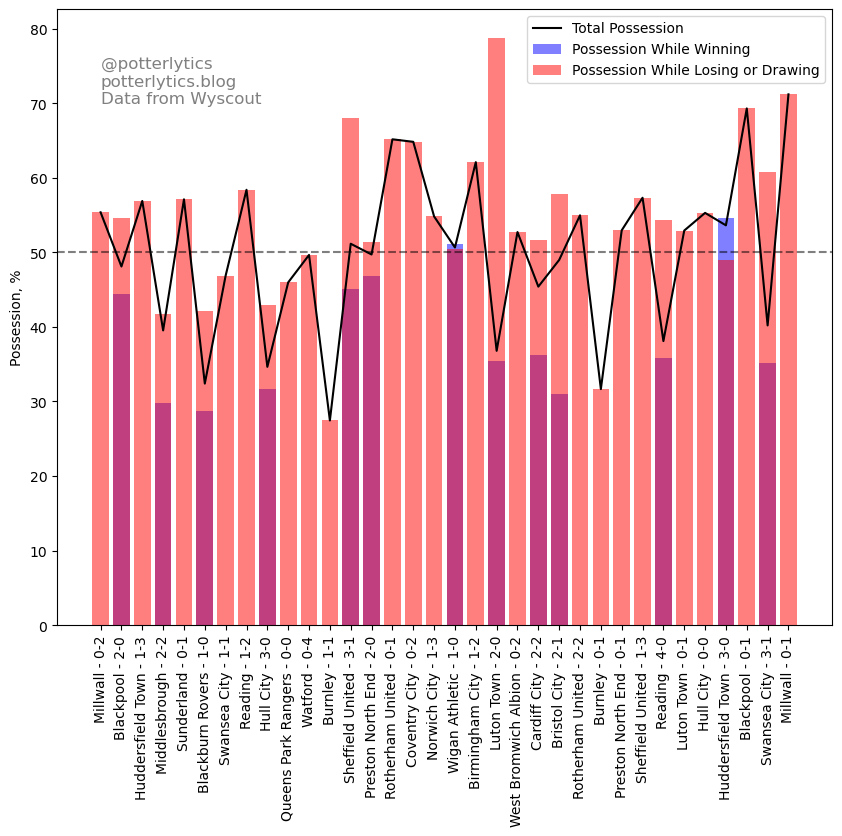

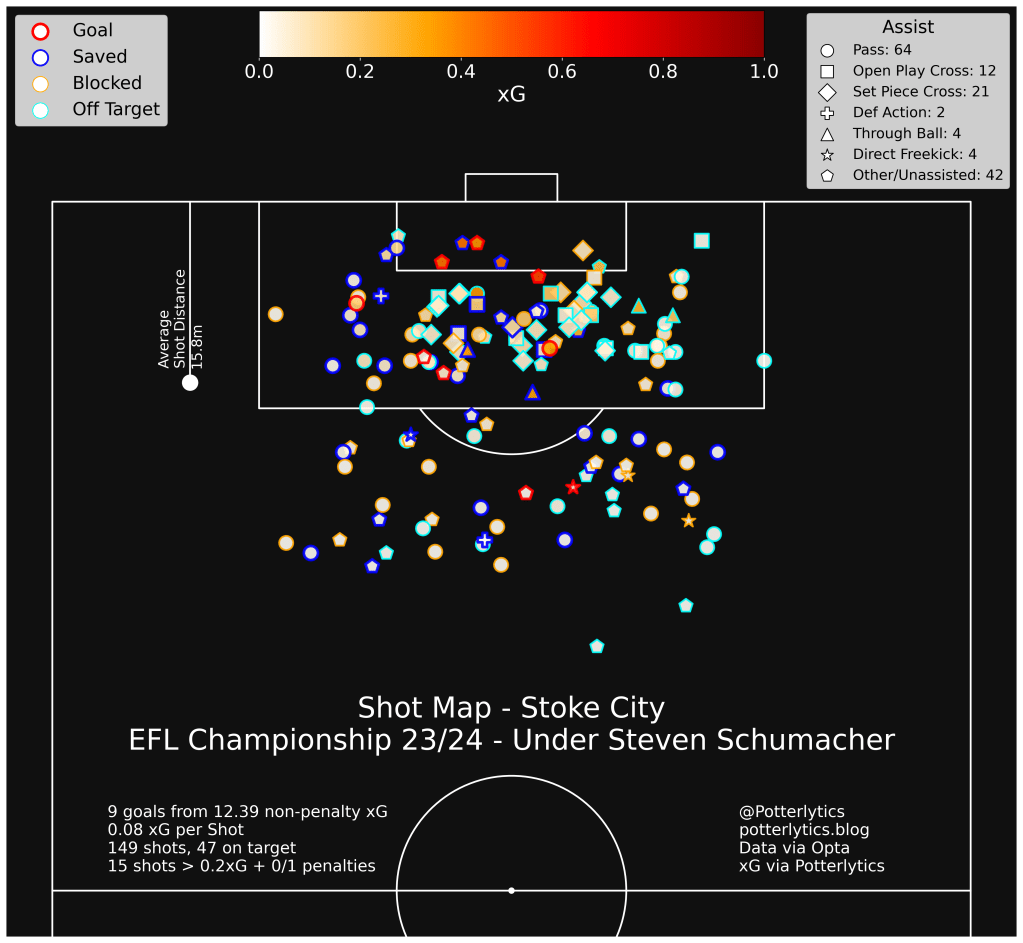

The rankings above give us a little insight into how Stoke have struggled in terms of their creativity and their finishing through the Schumacher reign. I’m in the process of editing a video about this now, so I won’t go into too much depth, but suffice it to say, shot selection and patience around the box is the main vein of thought in my mind.

We can see above that although Stoke take a decent number of shots, have a just above average xG, and about average number of ‘big chances’ (an often-misused stat in my opinion, but useful in this case), they also take a disproportionately high number of speculative chances (again, easily misused, but in this case simply indicating low-value shooting), and a similarly high number of chances are from set piece situations.

While set pieces and lower-value shots aren’t bad, having a high relative number of both types of shot can indicate issues in creating the types of chances that a more dominant side might aim for.

Combined with the low ranking in average xG per shot, we paint a picture of a Stoke side that tends to either create really good chances (such as those above), or hope that potshots and set pieces can save the day. The positive I take from Saturday is that we saw at least two occasions where we created very good chances from quality open-play patterns, something we haven’t seen too often since Birmingham at home.

Of course, the second issue evident in that plot is the finishing. Almost the worst in the division at converting xG into goals, and similarly poor at converting big chances into goals, and it doesn’t seem to be getting much better. The last 4 goals Stoke have scored have been a rebound from a free kick, a back post tap in from a corner, Niall Ennis’ fantastic finish against Blackburn, and an own goal.

There is some evidence this may change, however, as in 6 of the last 7 games, Stoke have amassed a post-shot xG (how likely a shot is to go in given where it’s aimed, how fast it is going, and the trajectory) at least 0.5 above the number of goals they’ve scored. Whilst not hugely comforting and slightly misleading in some cases, it does indicate that there is at least some element of poor luck involved.

Most crucial, though, in my opinion, is the selection of when and where to take shots, and when to look to patiently reset the attack or find another option from a supporting teammate. The two examples above indicate times where we’ve chosen our passes well, and to see a few times we haven’t, look out on potterlytics.com/patreon in the next few days!

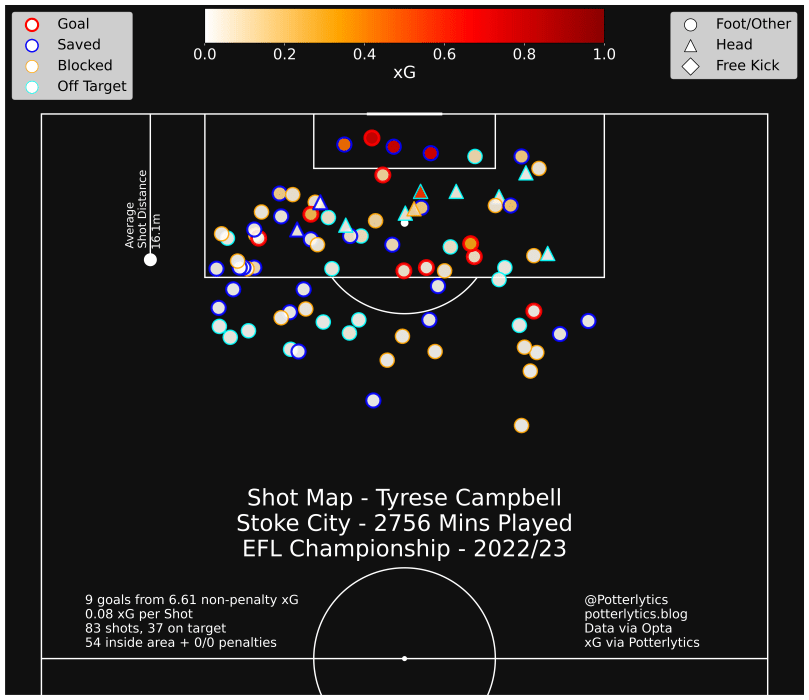

But in the meantime, here’s a look at all of our shots under Steven Schumacher.

A Game of Two Halves, Asterisk

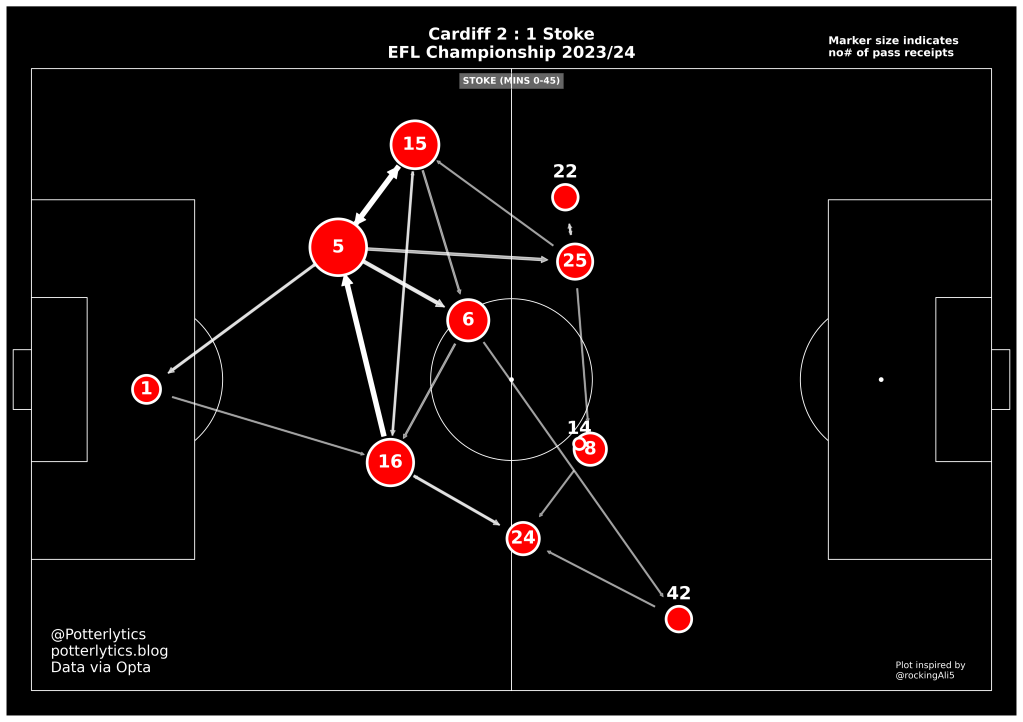

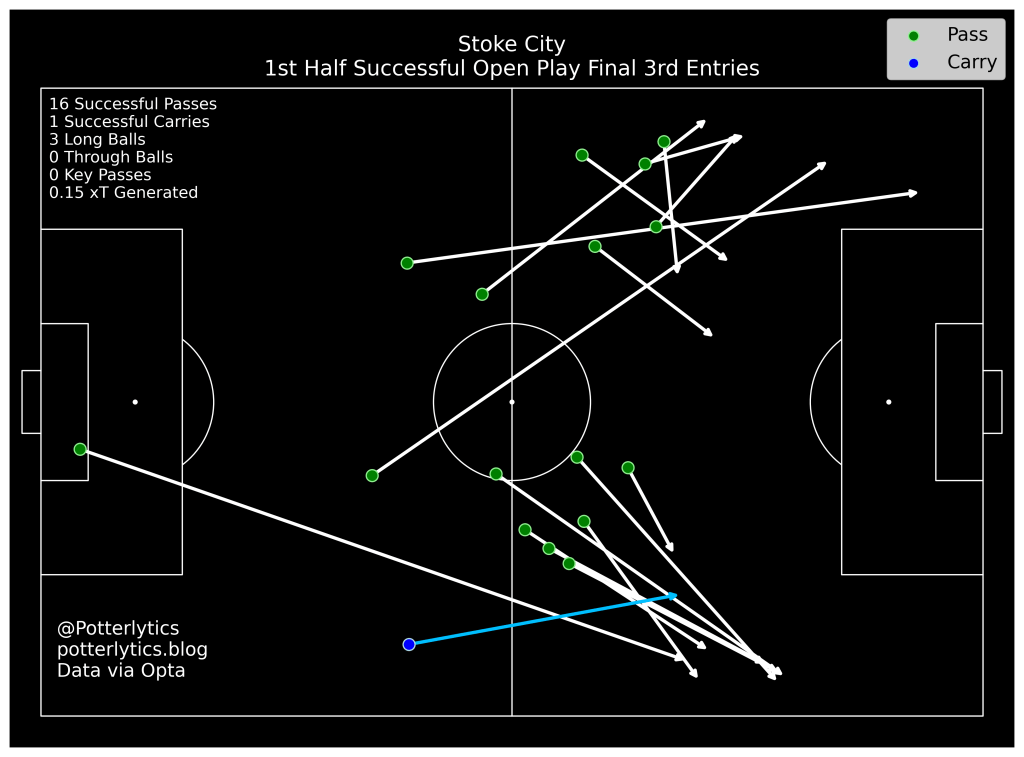

Finally, for the third or fourth game in a row, we’ve seen an improvement in how Stoke move the ball in the second half of a game.

Above we have the passing networks for both halves, and we can see that (despite the substitutes being in strange average positions) we’ve got a far better connection between the defence and midfield in that second half.

The play is much more balanced from the defence, rather than consistent play from right to left (and the less said about Thompson’s play in this match the better), and Baker was much more present to receive passes from the central areas than previously.

Now, you may be screaming like a frenzied, rogue Tifo Jon Mackenzie, ‘BUT GEORGE!! THAT’S JUST GAME STATE!!’, and you’re absolutely right. A big part of the improvement in play between the defence and midfield is due to Cardiff sitting deeper, and in fact didn’t lead to an improvement in chance creation or xG.

But there is something to be said for the improvement in confidence in passing in that second half, and although the play around the edge of the box was poor, there were signs that Stoke’s defence and midfield have the quality to play through an opposition press.

To that end, we did see more entries into the final 3rd and the box in that second half.

Now we just have to do something with it…

Thanks to any and all readers, and please feel free to comment and follow on Twitter at @potterlytics or watch out for the new long-form video content at Patreon.com/potterlytics. There’s already a video on Ben Pearson’s role in the side and a video coming soon on our woes in front of goal.

Should you wish to donate to help with the running costs of the site, and the data subscriptions we use, please feel free to visit our donations page here or subscribe to the Patreon linked above. Any and all help is very much appreciated!

George